Fractional reserve banking is a system in which only a fraction of bank deposits are kept on hand for withdrawals.

Banks use the rest of depositors’ money (outside what they’re required to hold as reserves) to make loans and generate profits. This system enables banks to lend considerably more money than they have on hand.

The money multiplier

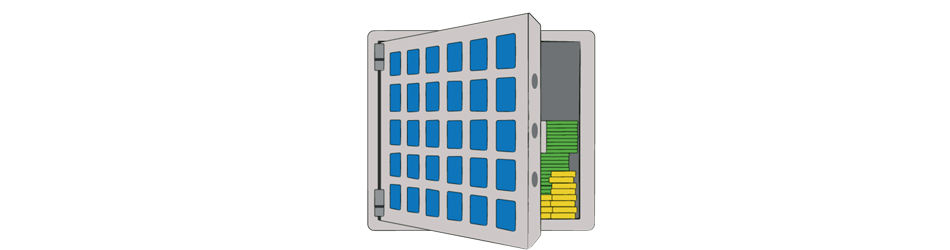

A bank loans (or invests) its excess reserves to earn interest. In a fractional banking system, increasing the monetary base by one dollar will increase the money supply by more than one dollar. Banks essentially create money by making loans.

The increase in the money supply is the money multiplier. The money multiplier is so named because it has a powerful effect; the less money held in reserves, the more money that can be made through lending activities.

The money multiplier is calculated by dividing 1 by the percentage required to be held in reserves. The norm is a ratio of 9:1 between money lent to the required level of bank reserves. In this case, the deposit multiplier – as it’s also known – would be 10 (1 / 0.10 = 10).

The money multiplier is a numeric indicator of the capacity for banks to make money and generate the profits needed to pay dividends to investors.

History of fractional reserve banking

Before the Federal Reserve was created, the U.S. government established its banking system with the National Bank Acts of 1863 and 1864. These set reserve requirements at an across-the-board rate of 25%.

When the Federal Reserve Act was passed in 1913, it gave the Fed the power to require lenders to maintain reserves. From 1913 until 2020, the mandated level of reserves varied from 7 to 13%, depending on the bank and/or type of account.

The Fed dropped reserve requirements in 2020, arguing that money was better used if freed up to lend, which would in turn stimulate the economy. It was an attempt to help shore up the economy after the Covid-19 pandemic, but it also meant U.S. banks were no longer required to maintain any reserves.

Canada, for its part, had phased out its reserve requirements in the 90s, while U.K., New Zealand, Australia, Sweden and Hong Kong also no longer have specific reserve requirements.

When depositors come calling en masse

Fractional reserve banking helped pave the way for bank failures during the Great Depression, when too many people tried to withdraw money at the same time. The end result was catastrophic for many, who lost their life savings.

The higher the percentage of deposits kept on hand at the bank, the lower the probability that depositors wanting their money will cause the bank to fail. But, maintaining a greater percentage of deposits means banks can’t make as much money from lending.

Fractional reserve banking is a global phenomenon

Fractional reserve banking is employed in virtually every country around the world. It strives to achieve the dual-pronged objective of ensuring that banks don’t run out of money while providing sufficient access to loans.

Fractional reserve banking is so widespread because it’s the only approach that allows banks to earn a reasonable and reliable profit. Without the ability to earn money on their assets, banks would have to fund their operations by charging much higher fees.

Alternatives to fractional reserve banking

Full-reserve banking is a system in which banks keep 100 per cent of all deposits on hand at all times. Having all of their deposits in reserves means that deposits are exactly where customers put them — in the bank. Of course, this means losing the key benefit of a fractional reserve system.

Instead of paying customers interest on their deposits, banks might charge (or charge significantly more) for their services. A full-reserve system could really only be enacted if there was an alternate means for banks to be profitable.

Currently, no country in the world has a full-reserve banking system in place for its deposit-taking institutions, although Iceland has considered it.

Recently, the Federal Reserve has also been exploring the possibility of a central bank digital currency. It’s in the preliminary stages, and given that its implementation could greatly affect fractional reserve banking, the Fed is carefully assessing benefits and risks, as well as seeking feedback from the public.

Fractional or factional?

While some advocate abandoning fractional reserve banking given the potential for a bank run, this risk is usually quite low. Others support sticking with fractional banking since further allocation of customer deposits ensures money is available for lending purposes.

A fractional reserve system means lower banking fees, higher bank profits, the ability for publicly-traded banks to pay dividends, and greater access to credit for those who need it. All of which are also good for the economy. So, which do you favour?