Anytime the Canadian loonie fluctuates, consumer goods like books and groceries can get more expensive.

The ire of Canadians was something to behold toward the end of 2015 when a weak loonie sent the price of strawberries up to as much as $8.99 a pint.

But it paled in comparison to the reaction from many consumers when cauliflower (unpopular as it can be) also spiked in price by early 2016.

It seemed that $7.99 for a head of cauliflower was just too much for people to take.

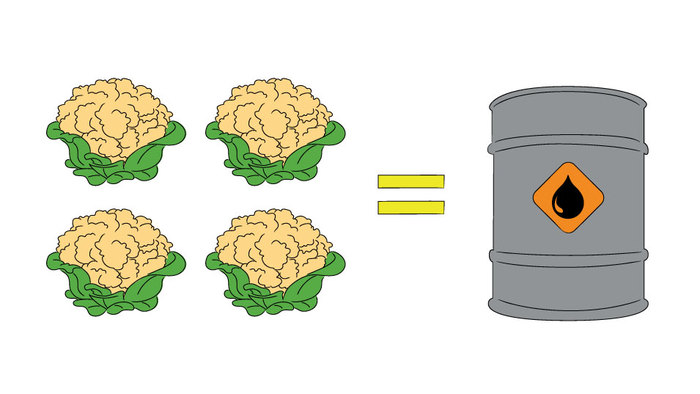

Maybe it was because The New York Times pointed out that at one point, five heads of cauliflower (around $40) cost more than a barrel of oil (West Texas Intermediate sat at US$29.69 at the time).

But the Internet went off, with memes joking about the kind of look you’d give someone who owed you money and who you spotted buying cauliflower, and editorial cartoons showing prospectors at an oil rig celebrating the discovery not of oil, but cauliflower.

The reason for the apparent price disconnect has to do with the value of the loonie relative to the U.S. dollar. Since so much of the produce eaten in Canada is imported, the prices of fruits and vegetables are very susceptible to changes in the loonie.

“Buying power has significantly been reduced as a result of a lower loonie and so to import products into Canada in American dollars – it will cost more for us to acquire these products,” said Sylvain Charlebois, a professor with the University of Guelph’s Food Institute.

And that, of course, is a cost that gets passed on to the consumer.

When it comes to fruits and vegetables, it’s not only the currency that can have an impact. Climate change, production and demand can also play a role.

But currency fluctuations are most likely to impact raw products first, which is why vegetables may go up as soon as there’s a drop in the loonie, but things like baked goods and processed food may not spike for another three or six months.

Clothes, travel, cell phone bills and even big-ticket items like TVs and couches will all eventually feel the aftershocks if the dip lasts long enough.

The good news is that in many cases, as a consumer, you can retain a certain level of control over your spending – perhaps even forcing retailers to absorb some of the cost if they see certain products aren’t moving off the shelves at the higher prices.

“You just have to be careful – be more diligent and actually understand what the price of the product really is, or at least know your benchmark, so you don’t end up paying more for a product without knowing,” said Charlebois.

“The cauliflower for example, at $7 or $8 – just don’t buy it. You can wait a couple of days and it will drop, or you can go to the freezer aisle. You can actually save some money.”