Many Canadians found themselves wondering, “Why is the Canadian dollar so low?,” when, in 2015 alone, the loonie sunk about 25 per cent to at a 12-year low below the 70-cent US level.

When that happens, it can take a long time before a currency regains strength – and there’s no guarantee that the loonie won’t fall further.

Like most sharp movements in financial markets, there isn’t a single reason for the move. In this latest scenario, plunging prices for practically all commodities (particularly oil), the U.S. Federal Reserve and worries about the health of the Canadian economy are all responsible.

Plunging Oil

The Canadian dollar started its downward trajectory in mid-2014, when it was worth about 93 cents US. That was when oil prices (as seen on the U.S. benchmark West Texas Intermediate) started to deteriorate, losing their perch above the US$100 a barrel level as American shale production surged and Saudi Arabia refused to cut production. These factors occurred at a time when a general global economic malaise was depressing demand.

International investors tend to look upon Canada as the resource-rich Great North, so if energy prices plunge, the loonie is going to go down because they fear that a weaker Canadian economy would force the Bank of Canada to cut interest rates. Their fears were borne out as the central bank cut its key rate by two cuts of a quarter point each during 2015 to help cushion the economy from the effects of sliding oil prices – and those moves further accelerated the loonie’s slide.

The Fed Didn’t Help

The U.S. dollar was already gaining ground against other currencies during 2015, including Canada’s, because of a strengthening economy. But it strengthened further on speculation that the U.S. Federal Reserve would finally move to hike interest rates away from near zero, where they had been since the 2008 financial collapse. The American central bank did in fact start hiking rates late in the year.

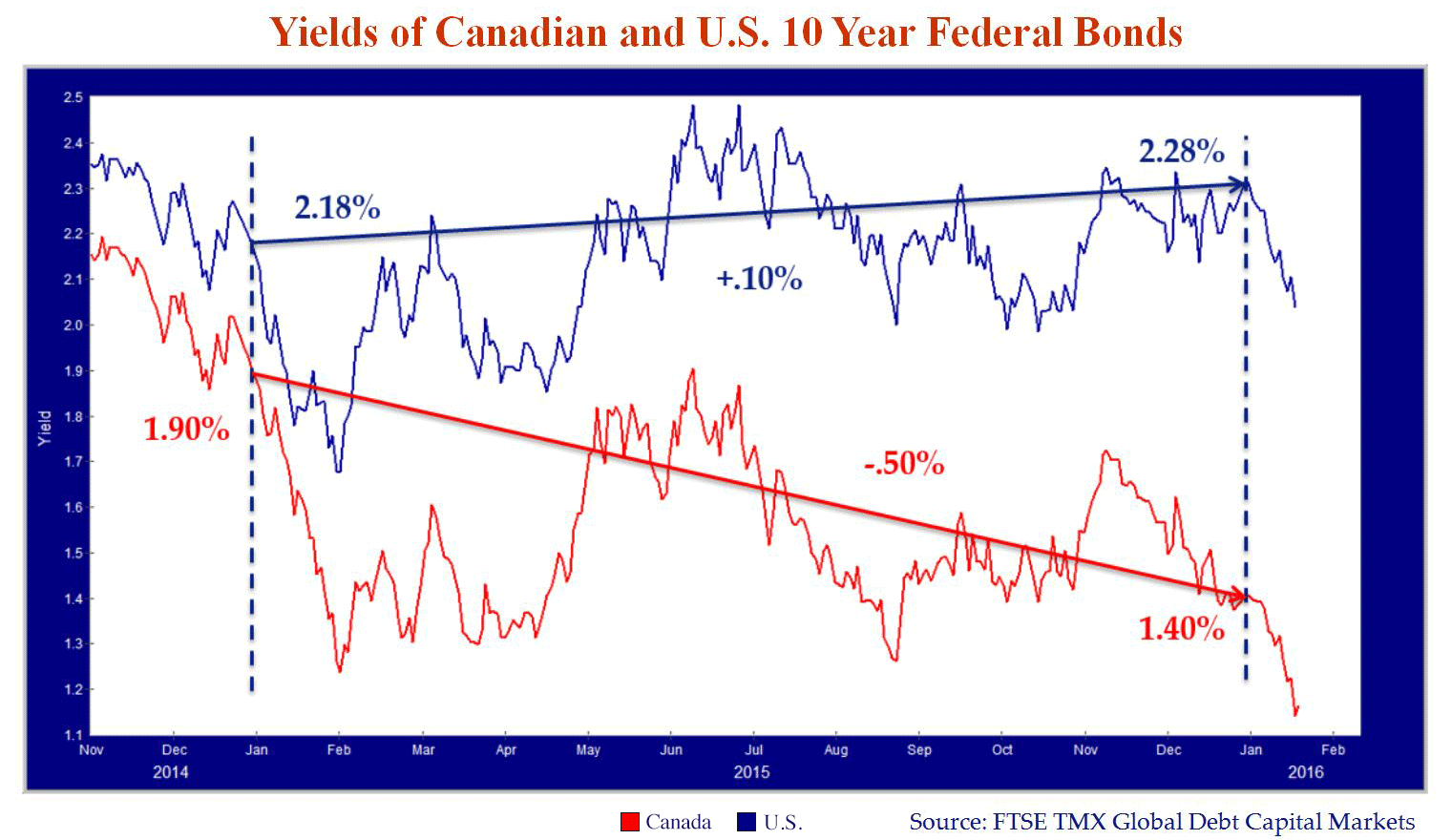

That translated into further strength in the greenback, at the expense of the loonie. That improvement in the U.S. currency is seen through high-yielding American government bonds. Canadian government bond yields stayed weak, with a spread of almost one percentage point compared to its U.S. 10-year counterpart.

And if you’re a central bank or a huge pension fund and you must invest money around the world, you have to have more money flowing into U.S. Treasuries because they’re higher yielding. And when you need to buy U.S. Treasury bonds, you need to buy U.S. dollars – and that forces the greenback higher. Putting further pressure upward on U.S. Treasuries is speculation that strong economic performance at home means rates will continue to go up while the rest of the world stands pat – or cuts key rates.

The Good and the Bad

No question, the lower loonie relative to the U.S. dollar hits consumers in the wallet. For example, agricultural produce like romaine lettuce or oranges are imported, making their price susceptible to the wobbling currency.

And that Caribbean cruise you wanted to take is suddenly a lot more expensive because many vacations southward are priced in greenbacks.

However, the lower Canadian dollar is a plus for Canadian exporters as their products have come down in price significantly for their American customers.

What Can I Do?

Here’s where it gets a bit complicated because a common method involves hedging. Simply put, hedging means you’re buying into a security to reduce the risks of negative price movements.

An airline might hedge its fuel costs by buying oil futures that are selling for less than the current price. For example, say the March price for crude is US$40 a barrel but the October futures price is US$30. You would buy a forward option allowing you to buy the crude at $30.

It’s like an insurance policy to limit the impact of foreign exchange risk and market pros do the same with currency.

Essentially, one company established a contract with a couple of other entities to more or less lock in a defined future rate of exchange in order to diminish the impact of currency fluctuations.

Another method might be to just keep a good chunk of your assets in U.S.-dollar denominated assets. But that strategy isn’t without risk – if you piled into a bunch of U.S. securities and the loonie rallied, you could be down 30 or 40 per cent.

It may be tough to remember another time when the loonie has lost so much ground, but it’s important to keep in mind that the currency moves in both directions.

In fact between 1990 and 2015, the loonie averaged about 81 cents US ($1.2346) moving between an average annual high of 1.011 cents US and a low of 63.67 cents US.

Things also happen quickly on financial markets. A sudden flare-up in the Middle East could spike oil prices up to, say, US$70 a barrel and suddenly push the loonie significantly higher.