The maple bond market had spent a pretty lonely decade going into 2017.

There wasn’t much love shown to this section of corporate bonds since the 2008 credit crisis turned the maple market into a small marketplace that priced out most supranationals, sovereigns and agencies and was instead focused on financial and non-financial corporate issuers. (Read: The Maple Market: What Is It and Why Would Issuers or Investors Use It?).

But in 2017, things started looking up. A lot.

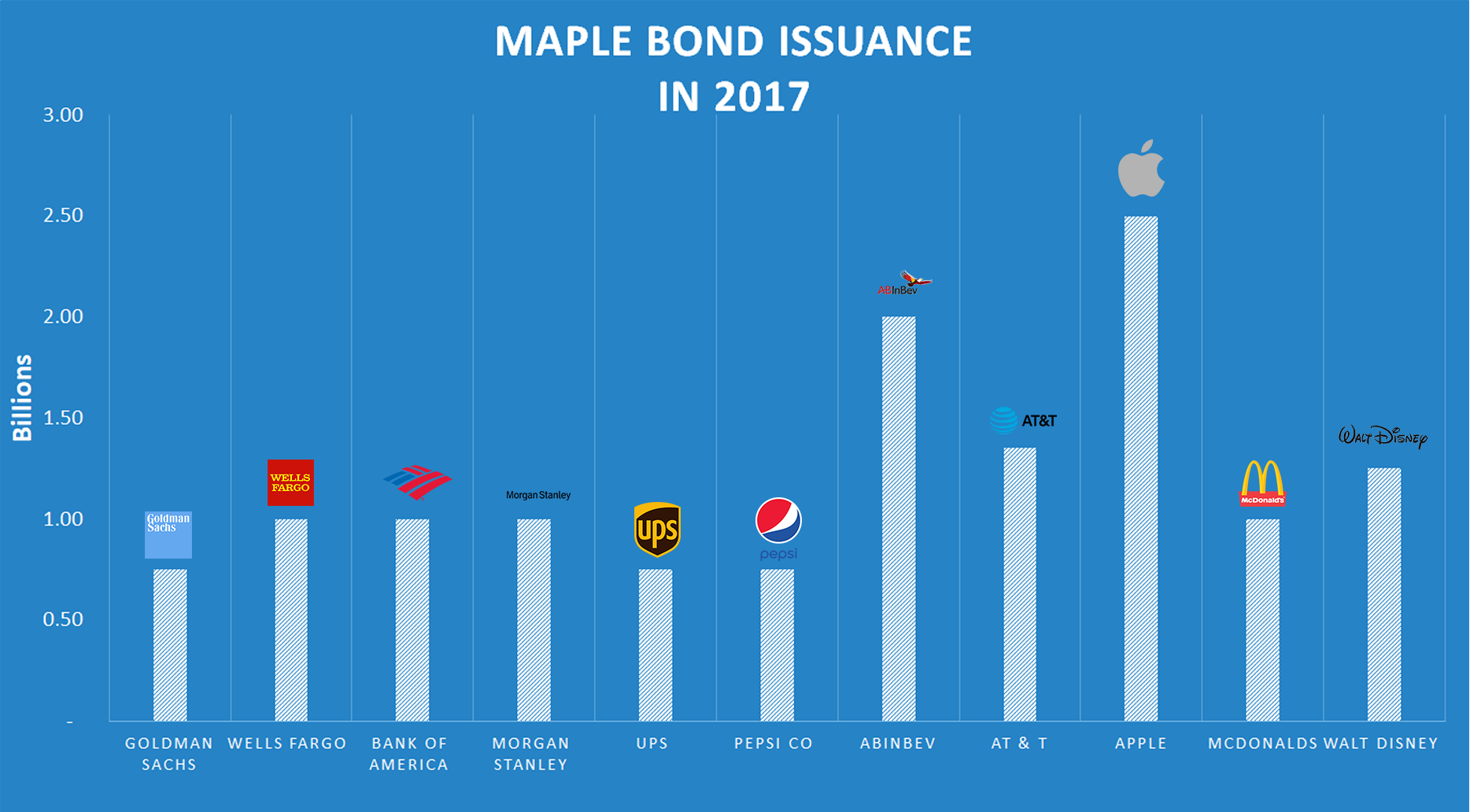

First, PepsiCo Inc. issued $750 million of seven-year securities, followed by Anheuser-Busch InBev SA, which came in with a $2 billion sale – Canada’s largest non-bank corporate bond offering since 2011 until Apple issued $2.5 billion in maple bonds three months later.

United Parcel Service Inc. followed Pepsi and Anheuser-Busch with its own sale of $750 million of seven-year securities, while AT&T Inc. issued $600 million of seven-year bonds and $750 million of 30-year securities.

About a month after the Apple deal, McDonald’s jumped into the fray, pricing $1 billion of bonds in September.

After a decade of low issuance, the maple market was reporting some of its healthiest months, thanks to a combination of attractive prices and increased demand. (Read: What Boosts Interest in the Maple Market?)

“The pricing works (and) investors are really interested in the true diversification that the Apple deal provided for them, plus a few other transactions, like Pepsi and UPS,” said Bradley Meiers, managing director and head of debt capital markets at HSBC Securities Canada.

“It feels a little bit different this time, and it feels like this pricing is likely to stay. I think the need for diversification is going to stay (as well).”

Market watchers remain cautious, but say the addition of all these new high quality foreign-issuers to the fixed-income market is a good sign for the corporate bond market, especially when you consider the fact that Apple was able to save several basis points on the deal by issuing in Canada.

“The deals at the beginning of the year were really because the Fed and the Bank of Canada were on two different interest rate tracks,” said Evan Dudley, an assistant professor of finance with Queen’s Smith School of Business.

“The Fed raised rates before Canada did, and I think a lot of the U.S. issuers jumped into Canada for that reason. Now that the Bank of Canada has raised rates (…) that advantage is going to go away.

But there’s certainly appetitive here for those kinds of issues in Canada, so if the pricing is right I can easily see more U.S. issuers tapping the Canadian market. It really has to be big name brands with a lot of investor recognition.”

The $2.5 billion Apple deal also demonstrated that the Canadian maple market could handle larger and more complex transactions than many foreign issuers previously believed it could.

“What was noteworthy with the Apple deal was the size of the transaction,” said Bill Girard, vice-president and portfolio manager with 1832 Asset Management.

“A lot of foreign issuers have not come to Canada because they just perceive it to be a small market where it’s hard to get significant size done. I think we’ll see more interest.”

To both Girard and Meiers, however, the one thing that can limit the market’s growth is the fact that maple bonds aren’t in the main part of the domestic bond index (the DEX index in Canada).

“These bonds are not in the main part of the index that the investors get measured against, so I think there’s only so much of their portfolio they’re going to want to be in these non-indexed bets,” said Meiers.

“I’m hopeful that the composition in the index will change, or that investors adopt the broader index that includes these maples, so they don’t always become non-indexed bets.”

“The market could potentially be limited by that, but right now, with the domestic issuance being down as much as it is, there’s definitely a spot for these issuers.

Personally, I think it’s going to continue as long as the market tone stays.”