When Apple decided to issue bonds in the maple market in the summer of 2017, the deal was greeted with open arms by Canadian investors thirsty for access to such a high-quality foreign issuer.

The diversification the deal gave institutional investors was clear, but what was behind Apple’s wish to tap into this relatively small market?

According to Bradley Meiers, managing director and head of debt capital markets at HSBC Securities Canada, the bank that led the issue, much of the deal hinged on the price.

By issuing in Canada, Apple could effectively finance the deal at a lower interest rate and then swap the currency back into U.S. dollars – money the company could use to fund a buyback that would help finance dividend payments to its shareholders.

It also meant Apple could pay out those dividends while avoiding the tax hit that would follow if the company tapped into money held elsewhere.

Back in May, Apple had said its Board of Directors had authorized an increase of $50 billion to its buyback and dividend program, which it was extending by four quarters. It plans to spend a total of US$300 billion to return capital to shareholders by the end of March 2019.

“It’s no secret that they have a large amount of money trapped overseas by tax policy in the U.S. that’s less favourable to them, so they’re borrowing this money (…) to fund a buyback,” said Meiers.

Apple has issued quite a bit over the last few years in the U.S., and the maple deal allowed the company to go into a new market and get new investors to diversify their base.

“As you start to issue more, you want to diversify where you can go,” said Bill Girard, vice-president and portfolio manager with 1832 Asset Management.

“If you’re well-known because you’ve done a couple of deals in another country, then if your own market either gets expensive or you’re a little saturated because you’ve done a lot of issuance, you can go somewhere else.”

It’s a move you often see with the Canadian banks, which will issue in the U.S. because if they did all those issues in Canada, their spreads would be a lot wider at home, he added.

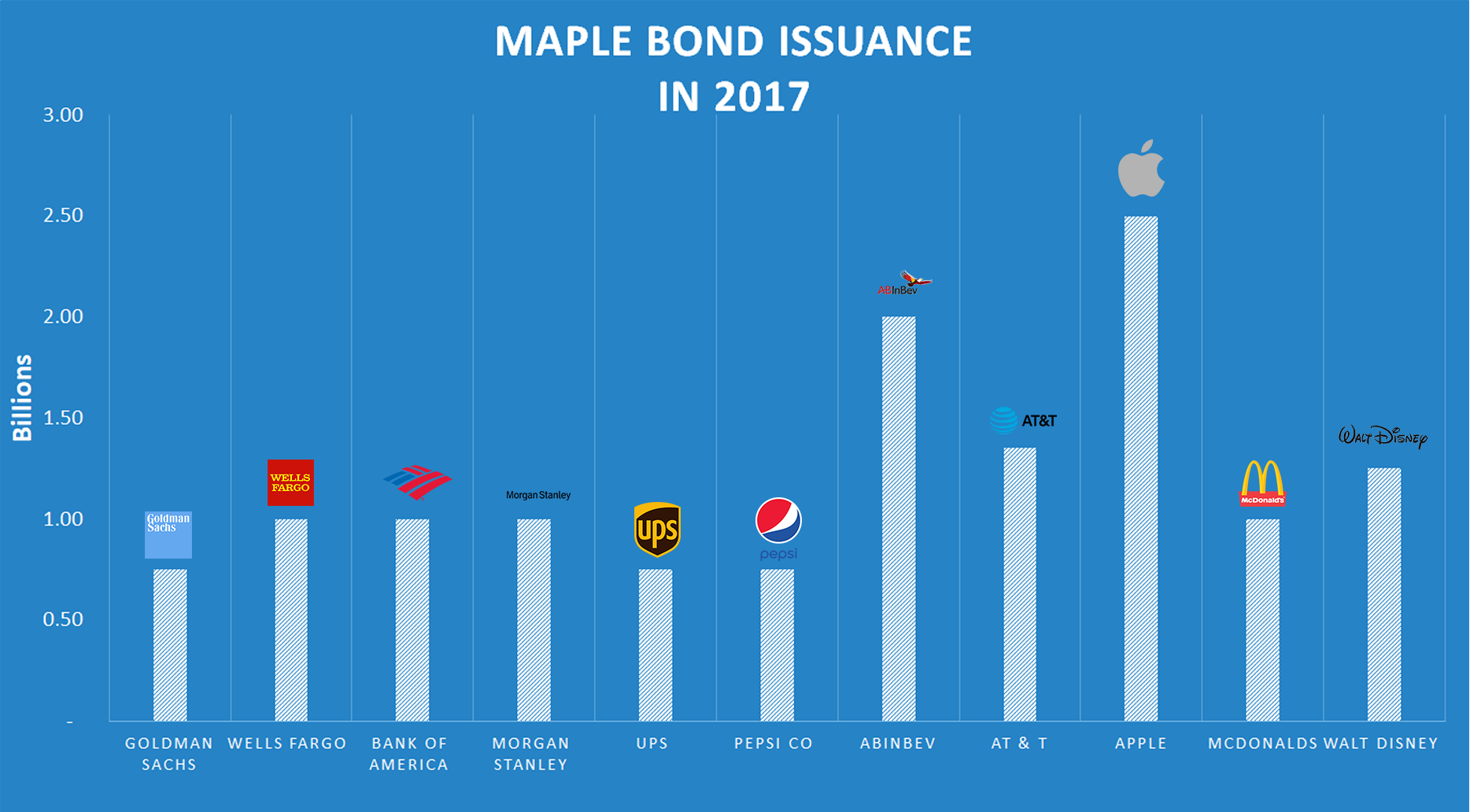

There was also a matter of timing. The Canadian maple market hadn’t been having much domestic issuance this past year, which has led U.S. firms like Pepsi and UPS to step in to fill the void.

Apple had looked at Canada in the past, Meiers, said, up until recently, the company wasn’t sure it could make the kind of deal in wanted in that market.

“They cared about the price, because that’s really their role as stewards for the finances of the company, but more importantly, I think they were impressed by the response from the Canadian market,” he said.

Evan Dudley, an assistant professor of finance with Queen’s Smith School of Business, the timing of the deal was also a factor. Apple issued its maple bonds before the Bank of Canada raised interest rates and before the Canadian dollar increased – all of which suggests the interest rate differential between Canada and the U.S. was a key motivator for the deal.

“From Apple’s perspective, this is a way to return money to shareholders in a cheap way,” he said.

“If you swap the interest payments back into U.S., with a currency swap, they (probably) figured (they could) save a couple of basis points, maybe more, relative to if it was issued in the United States.

One basis point (0.01%) on $2.5 billion with a term of about seven years – that’s a big chunk of money on the bond market.”