Investors’ emotional reactions – or behavioral finance — can have a huge impact on their level of success. But while most advisors can tell you that this happens, few have explained the science behind this phenomenon as well as John Coates, whose book, The Hour Between the Dog and the Wolf, details how our bodies react to risk when dealing with financial markets.

Behavioral finance speaks to the collection of behaviors and emotional reactions people may have while investing. These are reactions they may not be entirely aware of, yet they can guide a person’s investment decisions.

In his 2012 book, The Hour Between the Dog and the Wolf, physiologist and former Wall Street trader John Coates talks about the science behind behavioral finance and explaining how this phenomenon actually happens.

Wealth advisors can tell you anecdotally that investors are notorious for getting in their own way, and list the most common biases (link to our behavioral finance story here), but the reason why this actually happens comes down to biology.

According to Coates, a person’s fight or flight reflex, well known to be triggered when humans respond to risk and danger, also happens when dealing with financial markets. The physical reaction one’s body may feel when taking a financial risk, he argues, is not unlike what one would feel when being physically threatened.

If the person is winning, he or she will feel euphoric and develop a heightened capacity for risk-taking. If losing, they will struggle with fear and stress, leading to risk aversion.

That means that while biological impacts of risk on the body can provide the fast reactions and gut feelings needed for successful risk taking, Coates says these chemical surges can also overwhelm us, leading to irrational exuberance or pessimism that can destabilize markets.

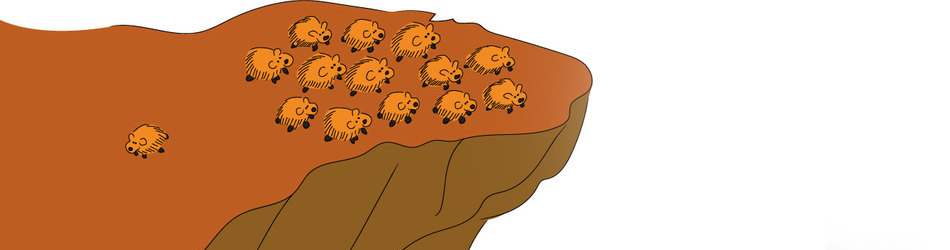

Much of the argument comes back to testosterone, the hormone that surges during times of danger, such as a fight between two animals in the wild. Testosterone flares up to provide what Coates describes as “chemical bracer” that increases the blood’s capacity to carry oxygen to the muscles. It also travels to the brain, impacting the animal’s confidence and appetite for risk.

The winner of such a battle will enter the next round of competition with an already elevated level of testosterone, which will help him believe that he’ll win again. But over time, this confidence and risk-taking behavior turns into overconfidence and recklessness – not unlike what you may see from young, male traders on an extended winning streak.

On the other side of this hormonal exuberance you’ll find cortisol, the main hormone of the stress response. Cortisol works with adrenaline, but takes a longer-term view. It slows digestion, reproduction, growth, energy storage and immune functions to retool your body after times of high stress, demanding a shot of glucose, which has by now been depleted.

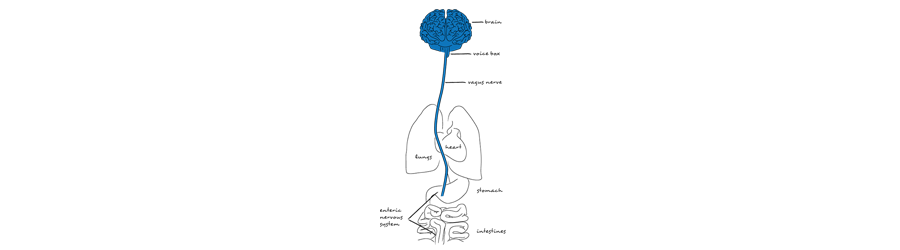

All hormones and signals are sent through our bodies through nerve fibers at such high-speed that people often fail to register them. You’ll often have the reaction without really thinking about why.

Our facial muscles will act first, followed by the visceral nervous system, which calls on organs such as the lungs and adrenal glands to help the muscles out. The chemical systems react last, releasing hormones like adrenalin into the bloodstream, giving us the burst of energy we need.

But if the challenge continues, steroid hormones like testosterone and cortisol take over; presumably to help us in the short term, and later, help us recover.

Sometimes, however, people don’t come down from these surges as quickly as they should.

That’s important when you consider research suggesting good judgment can involve a person’s ability to carefully listen to their body.

Coates points to a study by a group of psychologists at Florida State, which found that energetic resources during emergencies are distributed based on a “last in, first out” rule, meaning that the mental abilities that developed last in our evolutionary history, like self-control, are the first to be rationed when our glucose reserves are low.

Cortisol, like testosterone, can be beneficial in the short-term. But if cortisol levels stay too high for too long the person can experience anxiety, disturbing memories and a tendency to find danger where none exists. In financial markets, Coates says, this translates into irrational risk-aversion.

These steroid hormones, he concludes, can shift risk preferences systematically as they build up in the bodies of traders and investors.

If you’re a trader, the physiological impact of dealing with stress – in good or bad times – can contribute to a destabilizing effect in the markets.

If you’re a regular investor, it can mean you make choices that make you lose out on great opportunities or lead you to take on too much risk.

Behavioral finance impacts you whether you realize it or not – so getting to know yourself and listening to your body will help you make more rational investment choices.