The Canadian corporate bond market is the place where very large companies go to borrow money when they start to outpace their capital growth needs.

“If a company’s capital needs grow and grow, eventually you grow out of your banking relationship and you need other sources of capital,” said Evan Dudley, an assistant professor of finance with Queen’s Smith School of Business.

“It’s only the very largest companies, like Apple, that can do this.”

As a small business you can borrow from a bank, but that will eventually get expensive.

At some point, the bank will also start worrying about diversifying its pool of loans, since having one very large loan on its balance sheet is dangerous for its shareholders should the loan default.

If the company is medium-sized, it can look to the syndicated loan market, where the bank loan will be shared amongst different banks, or what’s called a lending syndicate.

The very large, highly-rated companies, however, will need to borrow more than what any one bank or bank syndicate can provide, so they’ll turn to the ‘public’ – which isn’t so much the public as in you and I, but rather institutional investors like pension funds and mutual funds.

In that case, the bank is just an agent or a go between the issuer (like Apple) and pension or mutual fund investors.

Small retail investors don’t really engage in the corporate bond market, because the transactions are too large and the bonds issued are often held for long periods of time.

That means the corporate bond market is less liquid than the stock market, with maturities running anywhere from one to 30 years – or in some cases, even longer.

“It’s certainly going to be cheaper capital, and from the investors’ perspective, you get to diversify the investor base – it’s not just one bank or three banks that are lending money to you; it’s many people,” said Dudley.

“For a $2.5 billion deal like with Apple, that’s just too much to swallow for one investor, at least one Canadian investor.”

The Apple issue, while corporate, was also what’s called a “maple bond” (link: What Is a Maple Bond)- a bond that’s issued in Canadian dollars and in the Canadian fixed income market, but by a foreign issuer.

Foreign companies will issue in a country like Canada if they want to take advantage of interest rate differential, manage taxes or diversify their investor base.

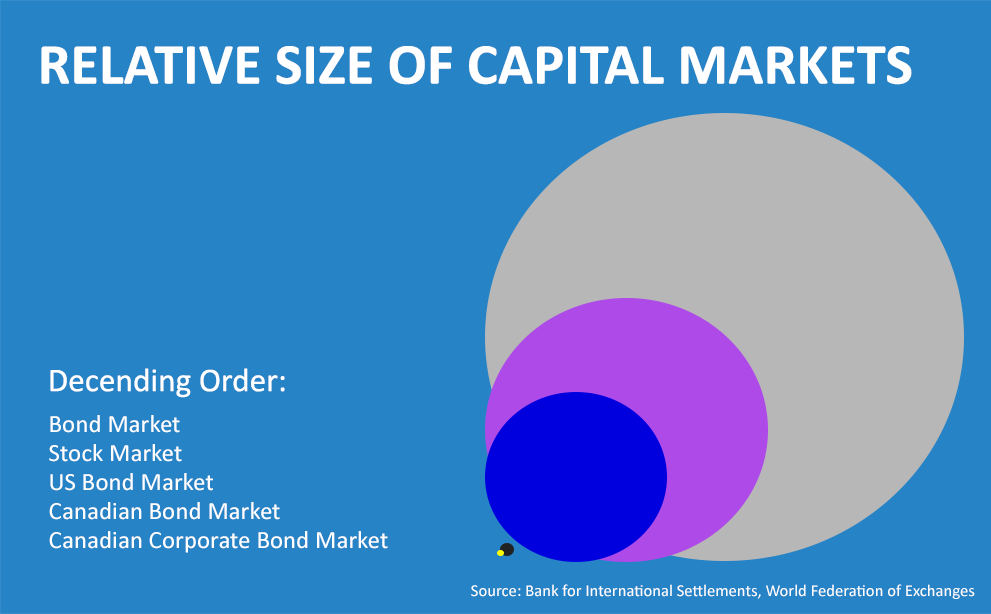

While the corporate bond market is part of the overall Canadian fixed income market, which was worth about $2.9 trillion in 2016, the corporate bond market itself is estimated at about $1.4 trillion (Source: Bank For International Settlements), compared to the $2.9 trillion that the stock market is valued at (As at August 31, 2017 – Source: TSX).

The maple market, which isn’t part of the main domestic bond index, is even smaller – but as the Apple deal showed, one that under the right circumstances, institutional investors can get really excited about.

Institutional vs. retail investors

If you’re not familiar with the world of finance, you may have trouble distinguishing between some of the key players. In the world of investing, size matters, and the kinds of deals available to you will vary depending on who you are.

Institutional investors are the big guns: pension funds, financial institutions like banks, mutual fund companies and even governments from around the world. This is where large bonds are traded, and it’s a market without a cap. Trades would be worth $500 million, $1 billion or higher.

Retail investors are much smaller – often individuals who buy and sell bonds with the bond trading desks of investment dealers, but the size of those trades is usually under $1 million.