The value of money and the rates at which you borrow it aren’t random.

They’re part of a complex web of numbers, markers and percentages that go into setting monetary policy and interest rate levels. But like any mathematical problem, if you get one number wrong, any calculation you make from that point on will also be misguided.

In 2012, financial regulators realized that one very big piece of one very important puzzle was wrong: LIBOR, the London Interbank Offered Rate, or the most commonly used benchmark for short-term interest rates in the U.S. and Europe.

It’s a calculation of the average interest rate each top London bank thinks it would pay to borrow money from one of the other banks, and it’s used to set everything from mortgage to credit card rates.

The problem with LIBOR was that while banks’ submissions should have been based on underlying transactions, there wasn’t a record of those transactions. The rates were estimates, so banks could theoretically submit false figures – and they did.

The LIBOR scandal revealed large-scale fraud and collusion by member banks when it came to rate submissions, with traders at several major banks submitting rates that were higher or lower than their actual estimates to influence the final average rate.

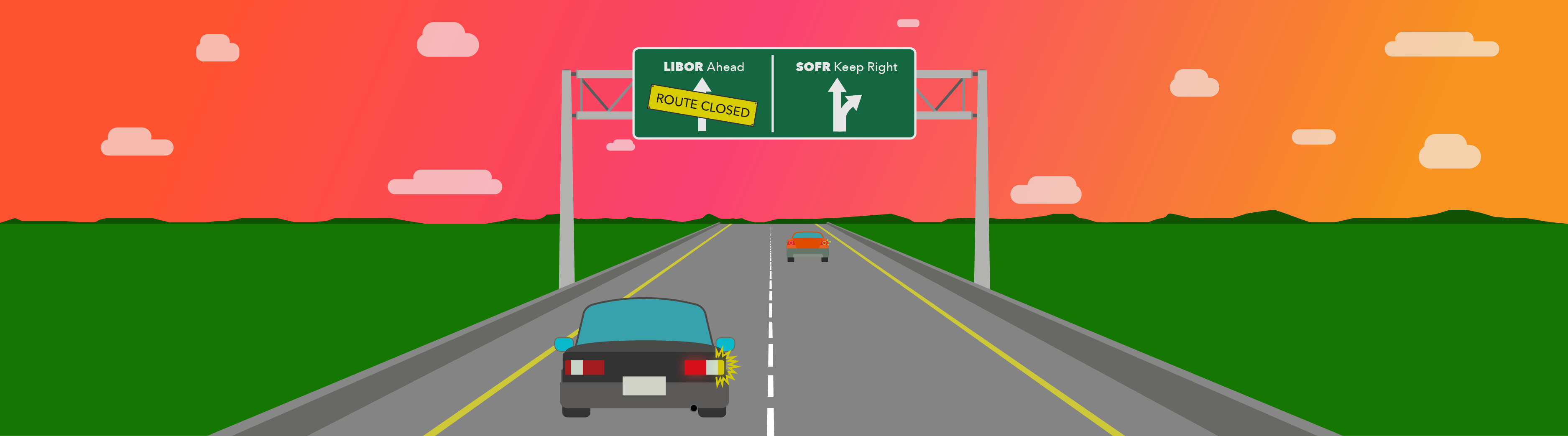

A revised version of LIBOR, based on actual interbank deposit market transactions, remains the main global benchmark in 2018. But LIBOR is on the clock – it will be removed in 2021 and replaced with another index.

The lead contender to take over LIBOR’s duties is the Secured Overnight Financing Rate, or SOFR. It’s a secured overnight rate based on Treasury repurchase agreement transactions and has a much higher transaction trading volume. That means it has more depth, but it also uses actual transactions – so it meets the key requirement for a benchmark based on “observable transactions.” Those transactions also come from broker-dealers, asset managers, pension funds and insurance companies – not just banks – so it’s a broader and more transparent index.

Fanny Mae, The World Bank and MetLife Inc. have issued a floating rate note and bonds, respectively, based on SOFR since it started being published daily in April 2018, while Credit Suisse was the first bank to issue debt tied to SOFR the following August.

The uptake was initially slow, and while it started gaining momentum by mid-2018, liquidity remained a concern. Some institutions also seemed unsure whether a switch is worth the trouble until they’re sure LIBOR will, in fact, go away in 2021 as promised.

The U.S. Federal Reserve’s Alternative Reference Rates Committee, which led the search for a new benchmark, has set out a multi-year transition plan for institutions to move to the new rate.

One of the big questions that remain is how these benchmark changes will affect funding costs – especially for outstanding debt that may now have to be serviced at a more expensive rate. It also remains to be seen whether the Fed will adopt the benchmark as its target rate instead of fed funds rate.

In Canada, a similar revision is underway for that country’s key benchmark, CDOR. While no wrongdoing has been proven with the Canadian Dollar Offered Rate, its reliability has also been questioned. A lawsuit is pending against several U.S. and Canadian banks over allegations they colluded to reduce the interest they would owe investors on CDOR.

The Bank of Canada is taking a close look at CORRA, or the Canadian Overnight Repo Rate Average, which, like SOFR, is also determined by actual market transactions, as a market risk-free benchmark that could replace or work along with CDOR.