There are various key benchmarks that banks and other financial institutions use to figure out the rate at which they should lend money.

In the U.S. and Europe, one of the most commonly used is LIBOR, or the London Interbank Offered Rate. It’s a global benchmark that affects the price of more than $370 trillion of financial assets across various currencies, and the main benchmark for short-term interest rates. Many banks, credit card companies and mortgage lenders will set their rates in relation to LIBOR.

LIBOR is basically the rate at which banks agree to lend to each other. It’s an average of the interest rate each top London bank estimates it would have to pay if it needed to borrow from the other banks.

It’s also seen as a measure of trust in the financial system, and of the confidence banks have in each other’s health.

One of the issues that has been raised with LIBOR is that the logic behind the agreed-upon rate is difficult to trace – the banks’ submissions may be based on underlying transactions, but there’s no real record of what those are. The rates are estimates, not actual transactions, so banks could theoretically submit false figures.

Those concerns came to a head in 2012 when the LIBOR scandal revealed there had, in fact, been large-scale fraud and collusion by member banks when it came to rate submissions. Traders at several banks were accused of conspiring to influence the final average rate by agreeing to submit rates that were either higher or lower than their actual estimates.

Several major banks, including Barclays, JP Morgan, Royal Bank of Scotland and Deutsche Bank faced hefty fines – for a total of more than $9 billion worldwide.

After the scandal broke, U.K. regulators took over from the British Bankers’ Association to ensure there was proper oversight, and an independent review suggested LIBOR submissions be based on actual interbank deposit market transactions – one of many recommendations the British government accepted and passed into law. Manipulating the benchmark was turned into a criminal offence.

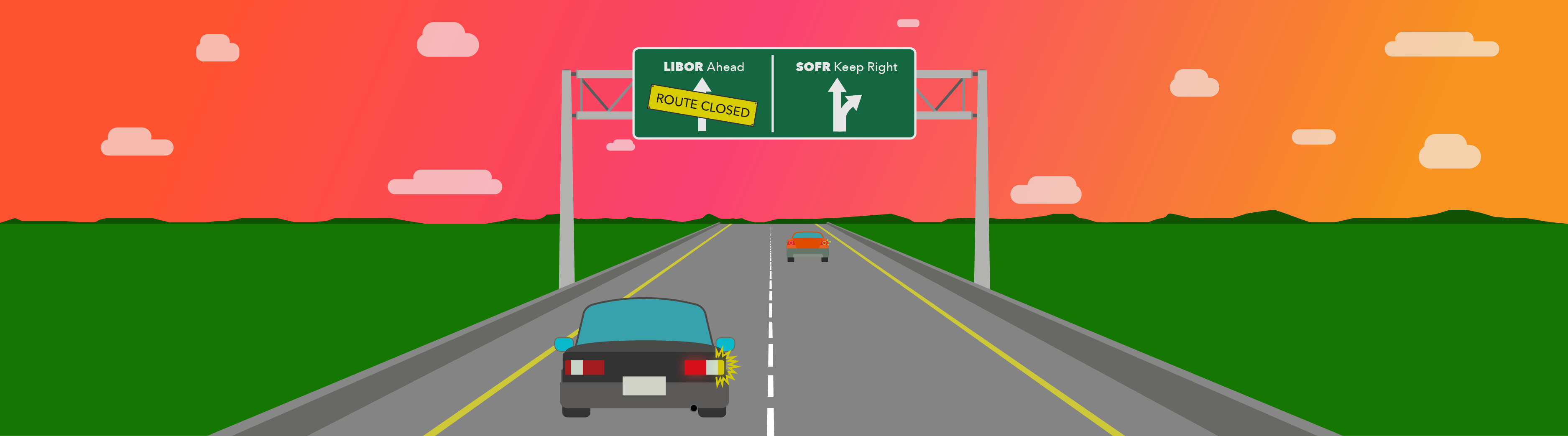

While LIBOR, in its revised format, remains the main global benchmark, authorities have promised to remove it by 2021, and some countries have already began moving to other indices.

In early 2018, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York announced the Secured Overnight Financing Rate, the Broad General Collateral Rate and the Tri-Party General Collateral Rate would replace U.S. dollar LIBOR as overnight interbank lending references.

Canada also promised to review its key benchmark, CDOR. The Canadian Dollar Offered Rate is also a short-term credit instrument, which provides the rate at which banks are committed to lending to companies. While no wrongdoing has been proven with the Canadian dollar-based lending metric CDOR, questions have been raised about its validity for years by investors and industry groups. A lawsuit is pending against several U.S. and Canadian banks over allegations they colluded to reduce the interest they would owe investors on CDOR.

The Bank of Canada is looking for a market risk free benchmark to replace or work along with CDOR, and is also studying a lesser-known index called CORRA, or the Canadian Overnight Repo Rate Average, which is determined by actual market transactions. The review is looking to broaden the volume of trades used to calculate those rates.