Bre-X is indisputably one of the biggest and most infamous frauds in capital markets history, and a rather unexpected Canadian tale of greed, gold and mystery. It began with a falsified gold find unlike anything seen before (or since) and ended with two mysterious deaths — which is perhaps why the Bre-X story remains fascinating more than two decades after the Calgary miner first became an overnight superstar.

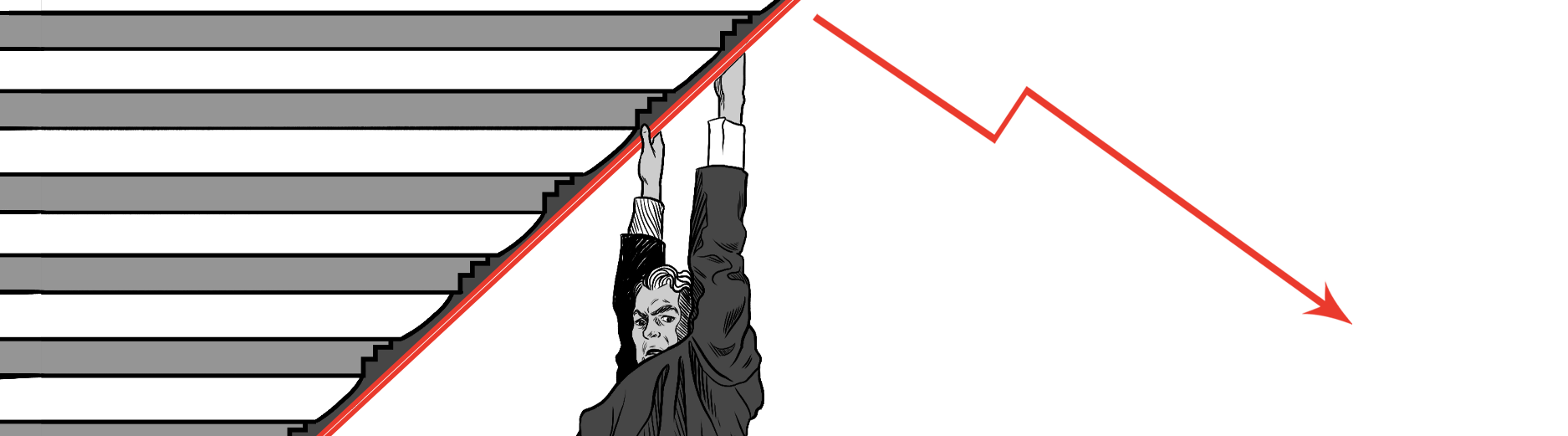

Bre-X was a penny-stock exploration company before it acquired an interest in what was being touted as the world’s largest recorded gold deposit in Indonesia in 1993. That “find” launched its wild ride on the stock market, catapulting its share price to $286.50 on the Toronto Stock Exchange and its market capitalization to more than $6 billion.

It all began when Bre-X project manager and lead geologist Michael de Guzman sent word from the depths of the Indonesian jungle of record gold finds — a geologist’s dream discovery. Problem was, it was a sham. In reality, de Guzman had shaved gold from his wedding band into core samples. When his ring was filed down to nothing, he purchased gold from local panhandlers, which he used to taint (or “salt”) the samples, for more than two years.

The president of Indonesia heard about this record gold discovery and wanted a piece of the action for himself and his people. The country’s long standing reputation of corruption in government and business meant that Bre-X would have to play ball if they wanted to operate in the country. While this remains unproven, it has been speculated that Bre-X may have bribed government officials — which might explain how the company was able to pull off such a massive scam. And despite how things ended, they did pull it off for some time. In fact, de Guzman and other executives became multimillionaires by cashing in some of their stock options before the whole scheme collapsed.

Ironically, this presidential involvement would ultimately be the unravelling of de Guzman’s plan. The Indonensian government decided to play hardball by pulling Bre-X’s mining rights until the company agreed to a deal that was acceptable to President Suharto. That deal ended up being one that would require Bre-X to share the Busang site with another Canadian gold company and have Freeport McMoRan, an American company, run the mine.

Freeport McMoRan wanted to send its people to the site right away for on-site due diligence. Once those samples were processed and no gold was found, the company wanted answers. But de Guzman would never make it back to address those questions.

While en route to Indonesia to meet with Freeport-McMoRan representatives, he disappeared from a helicopter over the Indonesian jungle. It took a few days for the body to be found, badly decomposed, in the Indonesian jungle.

There were rumours the body showed signs of torture, but nothing was ever substantiated. Interestingly, the National Bureau of Investigation in the Philippines – where de Guzman was born – had difficulty matching his fingerprints and confirming he was indeed the deceased. There are many people who don’t believe de Guzman died that day.

With no answers and no gold, the stock price quickly plummeted and didn’t stop until it hit zero. That was in March of 1997. By November of that year, Bre-X was officially bankrupt.

Founder and CEO David Walsh claimed to know nothing of the fraud. He subsequently moved to the Bahamas where he died of a brain aneurysm in 1998. Some people believe the Calgary promoter faked his own death and is living the high life on the lam — possibly with de Guzman.

In this case, both individual investors and professionals were duped, which was another unusual layer of this scandal. Most of the time, these scams target the former, given their more limited access to market information and lesser familiarity with industry procedures. Mutual fund companies bought staggering amounts of Bre-X shares during its heyday. OMERS (Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System) and the Ontario Teachers Pension Plan were amongst the biggest losers despite having extremely bright and investment savvy people looking after oversight of those assets.

Bre-X relied mostly on private stock placements, which meant less rigorous public disclosure requirements than if the stock was sold directly to the public. The only prospectus the company ever filed was from 1989, when Walsh first listed on the Alberta Stock Exchange. Bypassing public offerings meant there was not nearly the same level of due diligence or liability associated with direct sales to the public.

To put the Busang discovery in perspective, if Bre-X’s claims had been accurate, the company would have owned the rights to roughly eight percent of the world’s gold resources. Somehow, company officials were able to convince some 40,000 investors that they’d hit gold… and a lot of it. Ultimately, the scandal resulted in some beneficial changes to Canada’s market oversight and disclosure rules. But the more memorable Bre-X legacy has to be its place amongst the most nefarious capital market frauds in history -not just in Canada, but around the world.