Listen to our podcast episode on this topic, “What is an IPO?”

What Is An IPO?

An initial public offering, or an IPO, is a way for companies to raise money to fund or grow their business. They can issue equity or debt throughout their life cycle, but the IPO is the first time a company will sell its stock to the public – which is why an IPO is often described as a company “going public.” Until then, it is privately-held by its founders or private investors.

Why Do Companies Choose To Go Public?

Going public can mean access to a broader pool of capital, more level of prestige and a higher profile. But the move also comes with more scrutiny. Disclosure demands are high and regulation of public companies is tight. It’s in fact risen so much since the Enron scandal of 2001, that some companies have chosen to stay private to avoid spending so much time on tasks unrelated to their core business, according to John Horwood, director of wealth management at Richardson GMP in Toronto.

IPOs can also be expensive, given the number of lawyers, underwriters and investment bankers involved.

As a result, entrepreneurs looking to raise capital for growth will often turn to alternatives such as non-traditional financing, debt loans or private equity.

Smaller business owners can also look to sell the company privately if they’re looking at a possible IPO as an exit strategy, or do a private placement if they need to raise cash.

Why Would An Investor Want To Buy Into An IPO?

When an IPO is offered, investors tend to get excited. Many have the feeling they can get in on the ground floor, and become part of the story of a great company’s life as a public entity.

But, as Horwood notes, great companies often don’t make great investments, and a brand you love doesn’t necessarily translate into a good stock.

It’s also important to understand how an offering is being allocated among institutional and retail clients.

“It’s a very specific group of investors that do IPOs,” said Horwood. “The vast majority of them are taken up by the major institutions – the pension funds, those kinds of people are anywhere between 75 and 90 per cent of the market for IPOs.”

A small retail or individual investor won’t get a piece of the action until much later – if at all.

“The ‘ground floor’ happens with venture capitalists five or ten years before. They’re in the basement. The ground floor is the private equity guy who got in three or four years ago, now you’re a late stage investor, and the reason why people get excited is because quite often there’s a huge amount of selling and marketing that goes on with IPOs,” Horwood said.

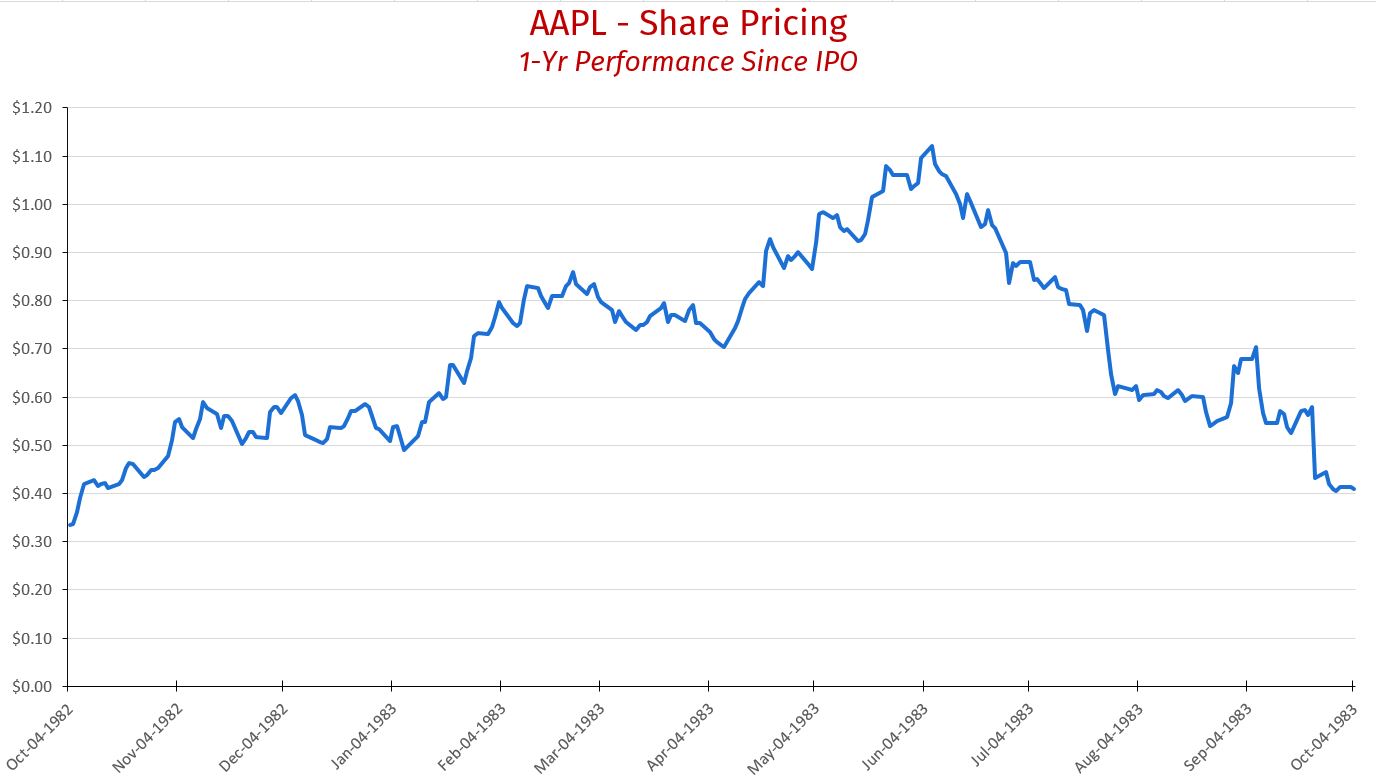

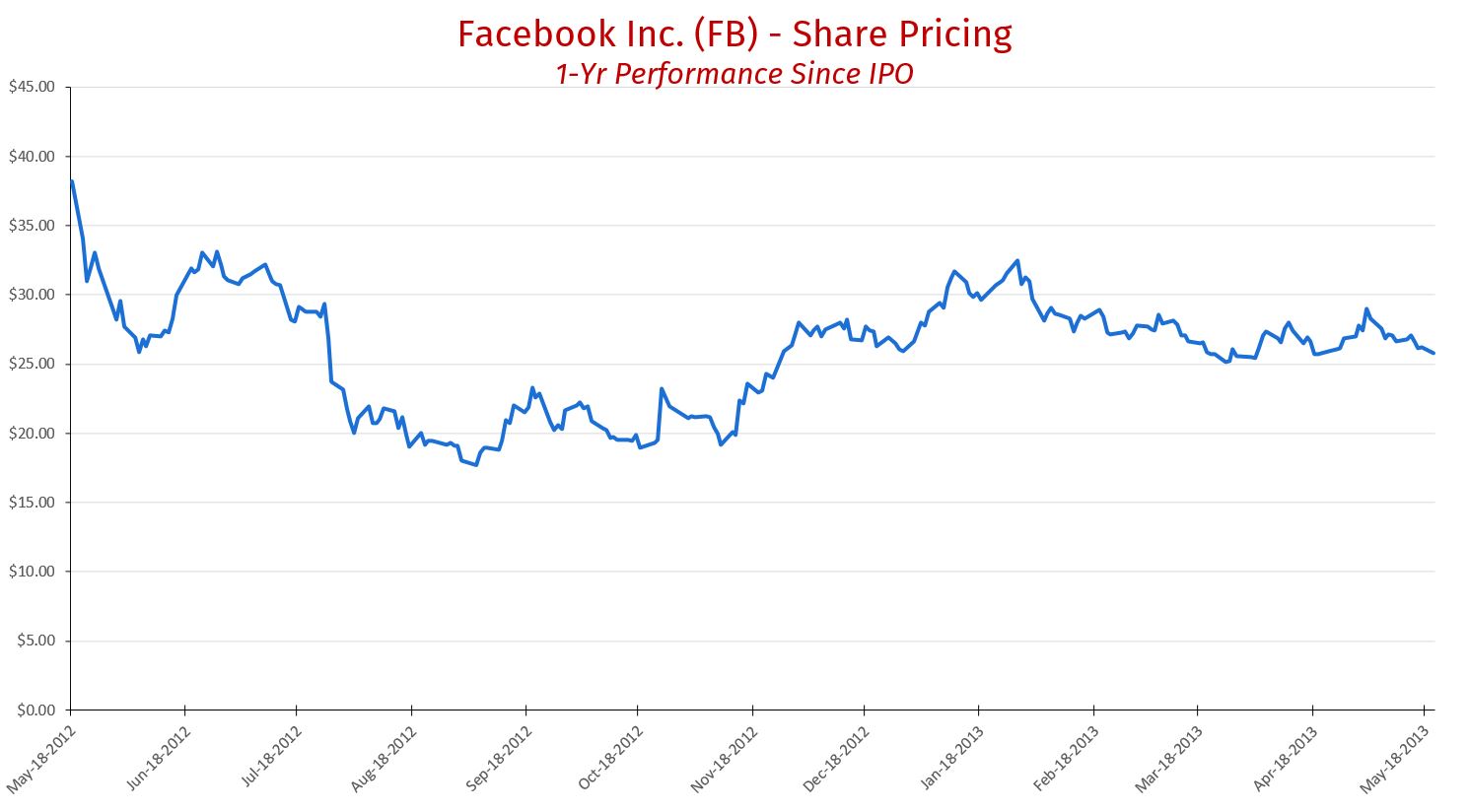

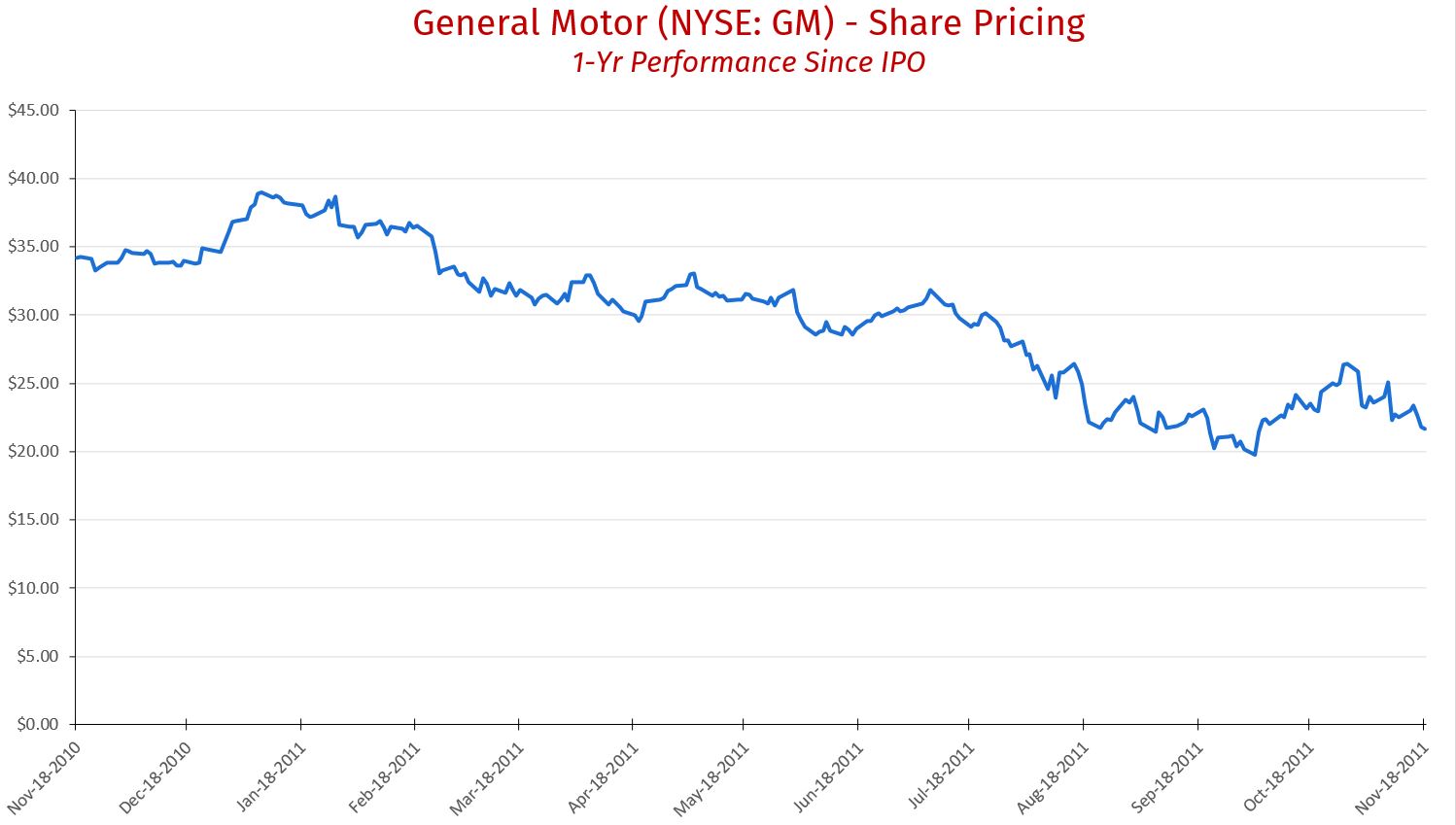

That means that for the average investor, who may have heard or read about an IPO, the best strategy may just be to wait, especially given that the IPO tends to represent maximum valuation of a company, and in six months or 12 months, the shares of that company will generally have traded down.

“Really, IPOs represent an exit strategy for private equity and venture capital people who want to exit the stock,” said Horwood.

“They probably held the stock for a number of years, they built it up to a viable business and now they’re looking to sell — and selling via IPO is typically the highest price they can get.”

There may be cases, however, when buying into an IPO does make sense.

But as with all the best investments, your best bet will be to do your research on the company before deciding to buy in, and talk to an investment advisor who can help you understand what you may be getting into.