Commodities trading has evolved hugely over the years. Much trading is based around futures contracts but not everyone uses them in the same way.

Commodity trading has come a long way since farmers in ancient times started to look for ways to keep prices stable as they dealt with totally unpredictable weather, warfare and the vagaries of supply and demand.

Things have evolved to a point where quite often, the commodity purchased isn’t even delivered and trading is used as a form of hedging to contain risk.

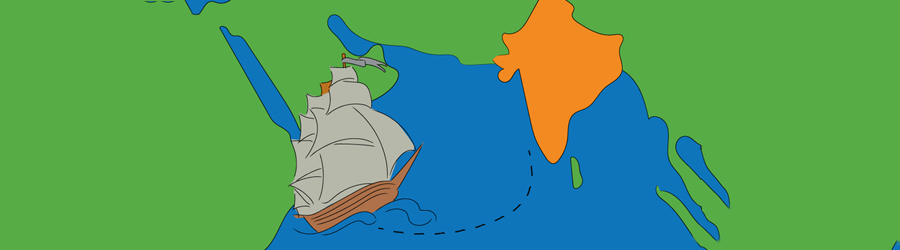

It is believed that agricultural settlements started trading commodities among each other around 8500 BC. Eventually, people started to explore methods of price preservation. As early as the 16th century, the Amsterdam Stock Exchange traded commodities and used sophisticated contracts including short positions, futures contracts and options. And futures trading involving rice took place in Japan in the 17th century.

Things got rolling in the U.S. a couple of hundred years later. The former Chicago Board of Trade (which became the Chicago Mercantile Exchange as a result of a merger in 2007) dates from the mid-19th century when farmers and dealers began to make written commitments to deliver specific amounts of grain for an agreed-upon price.

The essentials are still roughly the same but commodity trading these days encompasses much more than grain, which are in the group known as soft commodities and are made up of agricultural products including corn, coffee, sugar and pork bellies. Natural resources belong in the group known as hard commodities, and include minerals, oil and natural gas.

Commodities trading is based on what is known as the futures contract. Essentially, this means you buy a contract entitling you to buy an amount of a commodity for a fixed price at a certain time down the road.

This is all part of hedging, which is best explained as buying a form of insurance.

Futures trading isn’t confined just to commodities. They’re also sold for a wide variety of financial instruments including S&P 500 futures and currency futures.

When an investor buys a commodities contract, she doesn’t have any obligation to hold onto it until the expiration date and take delivery of thousands of bushels of corn. Many will exit the position well ahead of the expiry – some short term traders will hold onto the contract for just a few hours.

This trading takes place on physical trading floors in Chicago and elsewhere around the globe. But thanks to the huge expansion of the Internet in the 21st century, much of this trading also takes place in front of a computer screen.

Here’s an example of how futures trading works:

Let’s say it’s September and the price of gold is $1,400 an ounce. You believe that bullion is under-valued, thinking it will be worth more in the near future. So, you could buy a futures contract for December gold, which is priced at $1,500 an ounce. Let’s also say that gold has hit $1,600 an ounce by October. You could then sell the option back to somebody and make a profit. Obviously, the reverse is true if the price of gold drops. In the above scenario, you would lose money.

This represents an inherent risk – or benefit – in commodities trading in that price swings in either direction can be far more dramatic than is usually the case with stocks.

You can divide the futures market into those who hedge and those interested in speculation.

Those in the first group are seeking price protection while the second group isn’t interested in taking delivery of the product – they’re trading prices, not commodities. And they’re essentially placing bets on where prices will be in the future.

Speculation can be responsible for big price swings in a given product such as oil. But experts say speculation is a good thing as it makes markets more liquid than they would be otherwise.

Futures trading is heavily standardized. For example, buying a single soybean futures contract means you are sure about the future value of 5,000 bushels of the product. If you buy a pork bellies contract, you’re taking a position on 40,000 pounds of pork bellies.

Futures trading is also highly leveraged. That means that investors buy contracts for between five and 10 per cent down. This is quite a bit less than buying stocks on margin, where investors have to pony up around 50 per cent of the price of the stock.

Another difference is that investors buying stock on margin means financing a big chunk of the cost with borrowed money where interest is charged. But in futures trading, the up front money is really a performance bond with good faith signalled by the investor’s willingness to pay or deliver the full amount if the contract is held to its expiry.