Geopolitical events can have a big impact on oil prices, but anyone looking to invest in the oil sector would be wise to look beyond these headline-grabbing (but temporary) impacts and consider what’s likely to affect the companies in the longer term.

“Geopolitical risk has always been there and always will be but … it probably ranks lower on the minds of most investors given these other, more macro, longer-term challenges that the companies are facing,” said Lysle Brinker, Executive Director of equity research for integrated oil companies with IHS Markit in Connecticut.

Supply, demand and pipelines

One of the key factors that impacts oil prices, in good times and bad, is the interplay between supply and demand: how much oil is being produced to fulfil the needs of the market.

But for the Canadian oil sands, that’s also closely tied to pipeline access.

“Any additional production that comes online right now, you have to think really seriously about how you’re going to get it out of the market to export markets,” said Kent Fellows, an economist with the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy.

In 2019, Canada’s growth has also been hampered by legislation such as Bills C-48 (aiming to ban ships that hold more than 12,500 metric tons of oil from waters off the north of B.C.’s coast) and C-69 (which promises to evaluate future infrastructure projects based on their impact on human health, local communities and the environment) and “the perception worldwide is that Canada is not open for business on the oil side,” said Martin Pelletier, a portfolio manager at TriVest Wealth Counsel Ltd, a Calgary-based private client and institutional investment firm.

The lack of pipeline infrastructure and uncertainty around what, if any, proposed pipelines will actually be built means foreign companies are leaving and taking their capital with them.

“When you start piling on that we’ve had some pretty significant developments in shale oil in the U.S. – you have additional supply coming online and that depresses prices – it’s really adding bad to worse,” Fellows added.

Generational shift

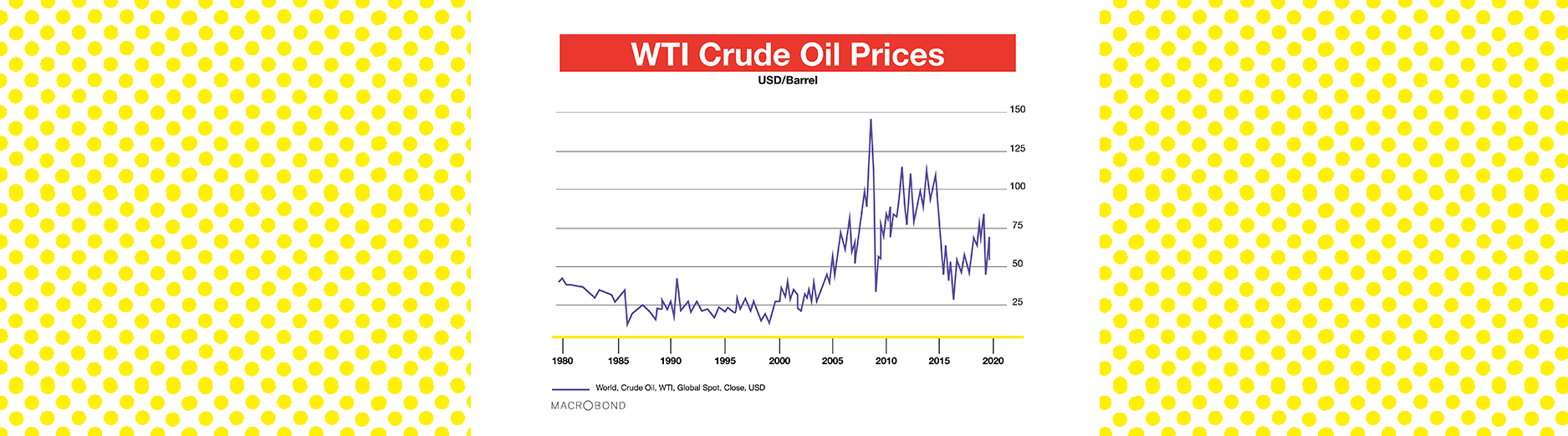

But while the U.S. oil sector has fared better than Canada’s, the North American sector as a whole is far from its peak, when oil hit $100 a barrel a decade ago.

For some fund managers, the drop in oil prices was enough to push them away from the sector, while for others the tipping point was the mismanagement of capital by the oil companies that failed to properly plan for growth.

“All these things are weighing in the investor’s mind and you’re having a generational shift in investment managers … (who now) have a lot more investment options,” said Brinker.

“I can’t remember a time when the sentiment has been so low and the challenges facing the industry in many respects, especially from an investment point of view, have been so many, and mounting.”

What’s next?

The negative sentiment doesn’t mean investors should stay out of the sector altogether. If you’ve done your research and can stomach the volatility, this type of climate can create buying opportunities: you’ll be able to get oil stocks at a discount.

But for the industry to bounce back, said Brinker, oil companies need to show disciplined capital investment by only putting their money into the best projects.

They also need to generate some free cash flow to return to shareholders, continue to pay down the debt they’ve accrued over the last decade, reduce costs, and pay (or increase) dividends to return cash to shareholders.

“To the extent that the poor sentiment is being met with more sellers than buyers of the equities means that if the company wants to support their stock price they probably need to be a significant buyer of their own shares,” Brinker said.

On a more macroeconomic level, interest rate cuts by the U.S. Federal Reserve are helpful for oil prices, as is a resolution to ongoing conflicts such as the trade war between the U.S. and China.

For Canada, a shift in government policy that signals the country supports oil and gas development would be key.

“The energy sector as a whole is not very well-loved in an environment where the yield curves are inverting and the economic outlook is recessionary,” Pelletier added.

“When times are good and commodities are moving higher (oil stocks) are cash flow machines.

But …volatility works both ways and so when the commodity rolls over … the profitability goes away because they require a lot of capital for re-investment.”