Investors can purchase securities in a publicly traded company by buying its equity.

If they wanted to buy a share of the common equity of Honeywell, for example, they could see the price at which it changed hands. They could access other information, including filings Honeywell made to regulatory authorities, or listen to management presentations. There are brokers who publish research on the company, and third-party services summarize the disclosed information in a more digestible form.

Valuing a stock

The decision to purchase Honeywell stock comes down to assessing the ability to sell it within a reasonable time period for an attractive rate of return.

To come to this conclusion, investors will predict the future value of Honeywell stock by examining its business, projecting its financial statements, valuing the enterprise, and estimating how the pie will get divided amongst all the stakeholders.

One way to value such a company is to discount the future value of estimated free cash flows back to the present and to compare that number to the market enterprise value. Of course, the forecast is uncertain. There is a band of confidence around the assessment that reflects the possibility the assumptions underlying the forecast are too optimistic or not optimistic enough. Ideally, for a big company like Honeywell, that confidence band is not too wide.

Valuing a startup

But without all that information available, how do investors in startups decide what price to pay?

For a private company, the investor may not have access to as much information. Even if it exists, it may be low quality. There may be less detail about the factors that drive the model, for example.

The bigger problem is the far greater uncertainty around whatever projections one might make.

There are, however, a few approaches investors can take.

Approach #1: Milestones

Starting from the assumption that the target company has the potential to become a unicorn worth a billion dollars in equity value one day, we can begin to think about milestones in terms of some underlying metric, like revenue.

At the billion-dollar mark, we might assume that there is no debt and no cash, so that the equity value is equal to the enterprise value. Further, we might assume that enterprise value is determined by multiplying revenue by some factor, say a factor of 10. This “multiple” reflects the strong growth in revenue one would require from a startup to get to this point in a period of seven to twelve years. A billion-dollar company with a revenue multiple of 10 implies run-rate annual recurring revenue (ARR) of $100 million.

Working backwards from unicorn status, we can imagine other ARR milestones: $50 million, $25 million, $10 million, $5 million, $2 million, $1 million.

These milestones map to different stages in the development of the company. A public company might have ARR of $100 million. We would say a Series Seed company has $1 million of ARR, a Series A company $2 million of ARR, a Series B company $5 million of ARR, a Series C $10 million of ARR, a Series D $25 million of ARR and a Series E of $50 million of ARR. Some companies raise subsequent rounds such as Series F or G. The term “Series” refers to a funding round. While every company does not necessarily do so, these are the natural evolutionary nodes at which it could execute a funding raise.

These revenue milestones correspond to the development of the business. At Series Seed, the startup can state, “People are willing to pay for my product.” At Series A, “I have obtained Product-Market Fit.” Each node represents a verifiable opportunity to accelerate the growth of the startup towards an eventual billion-dollar valuation with funding that enables the company to hire more people or develop more products.

There is a rough doubling of revenue from stage to stage. A 5% monthly revenue growth rate suggests roughly fifteen months to double revenue. Ten per cent monthly revenue growth implies doubling revenue in eight months.

Of course, the startup may generate positive free cash flow at each node in which case it can fund the steepening of its trajectory internally, rather than with cash from the outside that dilutes the capital structure for prior investors.

When the startup raises money, they may issue equity constituting between 15% to 25% of the post-raise equity, so this dilution can be substantial.

Further quantifying our example, a Series Seed company with $1 million of ARR at a 10x multiple has a “pre-money” value of $10 million. This is how much the company is worth without the new cash of the Series Seed deal. “Post-money” value is equal to the sum of the pre-money value and the funds raised in the latest deal.

If they sell preferred equity for $1.75 million in cash, then the new shareholders own 15% ($1.75 million of new money divided by the post-money value of $11.75 million) of the company. The continuing holders own 85%.

Similarly, if they sold preferred equity in exchange for $3.33 million, the new shareholders own 25% ($3.33 million divided by $13.33 million) and the continuing holders own 75%.

This approach is mechanistic, so it has the benefit of being simple and familiar. The biggest variable at each milestone may end up being the multiple that can fluctuate with market conditions, going up in frothy environments and falling in times of economic pullback.

Approach #2: Real options

The traditional milestones analysis starts with the belief that the startup is going to get to unicorn status and be worth $1 billion at some point in the future, following a deterministic path to glory as it hits its milestones along the way.

Of course, we have no idea if the startup is going to reach the promised land, or when it will do so. Growth could be lumpy. They might have hacked their early-stage growth to make it appear as if they had product-market fit when all they did was quickly obtain full penetration of a small market.

A better way to think about the startup may be to think of it as a bag of real options, as described by Market Business News:

“Real options theory is a modern theory of how to make decisions regarding investments when the future is uncertain. Real options theory draws parallels between the valuation of the financial options available and the real economy … a ‘real option’ is a choice available to a company regarding an investment opportunity.”

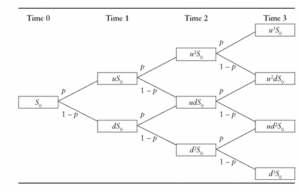

Before exploring this line of thinking, let’s talk about how to value options on the price of a stock, say GE stock. One intuitive way to value a financial option is to think of a binomial tree. This example is taken from a website called marketxls.

Starting today in Time 0, the stock price can go up or down. There are only two paths for it to take from any given node into the next period, hence the “binomial” nature of this model. It can go up with probability p or down with probability 1-p. If the stock goes up, we multiply its value at the prior node by the factor u. If it goes down, we multiply its value by the factor d. As it evolves through time, there is a spectrum of values the stock price can reach.

To value the option at Time 0, we start with the value of the option at each of the final end points and then discount it back through the tree for the time value of money, accounting for the probabilities governing its move from node to node. We do this until we get back to Time 0 at which point, we have a quantitative assessment of the value of the option.

We can do the same thing for a startup. At each node, the startup can either improve or hit a rough patch. Its revenue can go up or it can go down.

The startup’s revenue is a function of the decisions it makes at each node. For example, the startup could hire a new development team at a particular node or introduce a new product. The startup could add a new sales team or a new marketplace.

These decisions affect its path through the tree. They can even change the shape of the tree, by adding new branches on the upside, as the company expands its reach. The startup has options on options, or what some call compound optionality.

The ultimate value it will realize in the future is a function of the path the startup takes through the tree of possibilities.

One thing that pops out of this framework is that not all companies with equivalent revenue should be valued the same.

When Facebook had $1 million in ARR, it was much more valuable than Pets.com at $1 million in ARR because Facebook had many more available options to shape its tree to the upside. Facebook had a bigger target market, better management, higher potential margins.

It is extraordinarily difficult to understand both qualitatively and quantitatively the true real optionality of a startup. This is one reason people look for proxies. If you can find someone with a demonstrated track record of being able to do this (or the appearance of one), then investing in one of their deals makes sense.

Putting both approaches together

In practice, investors will adjust their multiples to reflect demand for a particular startup’s offering of securities at any given stage. A hot deal will see them chase prices higher, accepting fewer shares for their money by ratcheting multiples higher (and with it the pre-money valuation).

The multiples exist to summarize the real optionality that the startup creates with the strength of its management team, the size of its target market, the potential appeal of its product (and its extensions), and the strategy it employs to sell its goods or services.

The ideal situation for an investor to encounter is to see a large discrepancy between the real options valuation and the milestones-driven valuation the company is willing or compelled to accept. This is a scenario in which the supply and demand for the startup’s preferred equity is out of whack with its optionality. In this case, the investor gets a bigger piece of the pie than they would be willing to accept for the money they inject into the startup.

In future articles, we will talk about how investors and startups structure investing rounds.

Tying it all together

A key advantage of the milestones approach is that it is a way of de-risking the investment. Investors end up scaling up their investment as there is more evidence of traction and success. If it’s going to fail in the early stages, they wouldn’t have put too much funding into it.

One interesting comparison of the way a traditional investor approaches a situation like Honeywell to the way a venture capitalist looks at a private startup is that the traditional investor focuses on what could go wrong while the venture investor hones in on what could go right.

The traditional investor is trying to understand the uncertainty around their projections and financial forecast because there is already a great deal of value in the name that can go away. Honeywell is a $141.6 billion market cap company.

A venture capitalist tries to understand not only how the startup team can pursue non-linear paths through the company’s evolutionary tree that are in the upper half of outcomes, but also how the startup team can add additional branches to the upper half of the tree. It’s a small amount of money that goes into a venture company so there is limited, bounded downside risk and tremendous upside risk.

This is the fifth of a series of articles about startups and venture capital, where we’ll explain some of the concepts people might see discussed in the press. We’d love to hear your feedback.