Startups are capable of creating massive transformational change, but for a product to go from idea to reality, someone has to fund what’s essentially an experiment to test a hypothesis.

That money will either come from the founders themselves, who put in some combination of cash and uncompensated labour, or from outside investors.

Companies that manage to get by without doing much, or any, third party financing are said to “bootstrap” themselves. They pull themselves up by their bootstraps. Those that do raise money from individuals, including friends and family, are said to raise “angel” funding.

The funding tradeoff: speed and control

If a founding team can manage to bootstrap, it avoids reducing its proportional ownership in the new company, or “diluting” its equity ownership. In doing so, the team retains full control over the budding enterprise – nobody can tell them what to do or question their decisions.

The moment a company raises money from outside sources it must begin heeding the advice of the people who invested. These may be individuals who are not intimately or directly familiar with the problem being addressed, the details of the proposed solution, or the nature of customer sentiment. The founders’ attention gets diverted from focusing on their customers to keeping their investors informed and happy.

Founders who can’t bootstrap also end up with a smaller ownership interest, because their investors get a cut.

For the entrepreneur to accept this dilution and reduction in control, they must believe that the additional funding and assistance can accelerate growth in a sustainable, risk-reducing way, or the tradeoff may not be worth it.

Raising money to make money (faster)

In fact, the twin purposes of the investment are to pull forward and to make the startup’s survival more likely so that it can grow and generate meaningful positive cashflow (either on an ongoing basis or from an acquisition).

A startup is a portfolio of options with an indefinite exercise date and an indefinite strike price. The right investment pulls forward the in-the-moneyness of these options and creates more options, so that everyone can realize more value, faster.

In the early stages, founders shouldn’t worry about who will buy their company or whether it can issue shares to the public; they need to focus on making it something that somebody would want to buy (either as a takeout or as a public equity) and on getting to that place in a reasonable period of time.

If the investment case meets this threshold, then from the perspective of dilution, it’s better for the founding team to have a smaller piece of a much larger pie.

It also follows that, in that scenario, the value of the influence the minority investors exert makes the upside outcome larger and more secure, so the sacrifice of marginal control is more than justifiable.

But those are big ifs. What can go wrong with taking money? And what are the pitfalls of bootstrapping?

Risks and pitfalls

Scenario #1: You don’t need the money, but you raise it anyway, for the wrong reasons

Startups should not raise money just for the sake of raising money.

There are some founders who appear to judge the success of their ventures by their ability to raise large amounts, without thinking about what it might mean for their prospects of a successful exit.

These investor-oriented founders see their fundability as a validation of their business models and technology (or even themselves). But the true, direct proof of a company’s worth takes years to establish. Can you build a business that someone wants to spend a big chunk of cash to acquire or that public markets think deserves a high valuation?

It may be neither necessary nor sufficient to raise money externally if the objective is a big exit. Yahoo! raised a total of $6.8 million in funding over two rounds before reaching a peak market capitalization of $125 billion. Investors put in close to $400 million in Webvan before it went to zero. Theranos raised over $400 million in funding for technology that didn’t deliver. Before going public, Google raised a whopping $25 million.

Funding does not guarantee success and low levels of funding don’t mean certain failure.

Scenario #2: Raising money leads to bad decisions

It’s exciting building a company. It’s stressful, too, especially when the company doesn’t have a ton of money in the bank. There are people who depend on the founder to pay their salaries, to keep the office lights on, to give them the resources they need to build a product or deliver a service that will enchant customers, and to recruit those clients in the first place.

Raising money is a relief from much of this stress, at least initially.

The risk here is that the money starts to burn a hole in the founder’s pocket. The company raised it and took the dilutive hit to accelerate and stabilize the growth trajectory. If the founder starts to spend too quickly and too aggressively, they might misallocate the capital by using it for things with a low return on investment.

Alternatively, if there is a pace of organizational evolution that management can handle and if someone starts to exceed this rate by hiring too quickly or recklessly, then the culture of the firm can suffer, destabilizing the growth trajectory.

There is an optimal amount of money to raise at every stage. For long periods that amount may be zero.

Scenario #3: Raising money puts you on a treadmill

It is one thing to raise money from angel investors. Many of them are individuals who have mentally written off the investment to zero the moment they gave it to you. They may be investing for non-pecuniary reasons such as friendship or familial support. Most of them are unlikely to invest in any subsequent funding rounds.

It is another thing altogether to raise institutional venture capital from dedicated funds. These firms have finite lifetimes and return targets that they need to hit.

That means that these firms will want to put more and more money into the company if it is doing well, either from the current fund or from subsequent funds that they raise so that they can get to a larger percentage ownership (or at least to mitigate their dilution from later rounds). The founder may not want to take money beyond one or two rounds, fearing the dilution, the loss of control, and the potential distortion of decision making that higher capitalization entails. It creates a potential conflict of interest.

It also means that because these firms have finite lives of seven to 10 years, institutional capital is in a hurry. They must return capital (and, ideally, capital gains) to their limited partners at the end of the life of the fund. (Perhaps they can pass through the preferred equity representing their investment to the limited partners on a pro rata basis.) In their haste, they will suggest or even force managerial decisions to accelerate an exit that destabilizes the trajectory to the point of failure. Or they may push for a premature exit in which the bulk of the value flows to the strategic buyer but allows the VC to claim a high internal rate of return by compressing the time frame. Venture funds are in the business of raising capital; the rates of return are the means by which they do that – and it’s another potential conflict of interest.

Scenario #4: Raising money from the wrong people

When a management team raises money from external investors, they are going into business together. Often, the larger investors in a round will demand board seats (or board observer status). They will seek regular access to firm leadership during which they may try to influence decisions.

The right kind of investor knows how to handle the tension between advising the company and distracting them with too much interference. The wrong kind of investor is like a bull in a china shop seeking to run the firm. If things go well, they take the credit; if the situation becomes pear-shaped, the problematic investor blames the management team or the challenges of succeeding with startups.

In the worst case, there are investors who will hold up deals, either out of incompetence or greed. There may be times when a company needs to complete another round of funding, or put in place a partnership, or hire a key executive quickly. These are strategic decisions that require board approval and potentially, depending upon the terms, the approval of certain key investors. It could be that the investor cannot move fast enough to address the requirements of the moment. Or, nefariously, the investor may pursue hold-out behaviour, slow-walking their cooperation in order to extract unwarranted additional value for themselves by delaying or refusing to do what is in the best interests of the company.

Scenario #5: Bootstrapping can slow growth

Bootstrapping typically means the firm has less capital than it would have if it raised outside funds. It has less money to invest in bringing products to market faster or hiring new staff for sales to lift the revenue trajectory in a way that is more robust and self-sustaining.

Ideally, the right investors can help with introductions and coaching so that the management team can get on the optimal path to growth, one that is strong but still manageable. Bootstrapping takes this off the table.

It can make the firm riskier because there’s a reliance on employees to live on typically lower-than-market compensation for longer, bound by the promise of a big payday at some indefinite date in the future. Should key employees decide that date is too uncertain, they may leave for greener pastures in a self-fulfilling vicious cycle of dwindling growth prospects that beget further employee departures.

The announcement of a transaction, which tends to bring with it positive press coverage, or a securities filing that appears to validate the company’s offerings to potential customers, doesn’t happen with bootstrapping either.

There are no easy answers

Tradeoffs are tough, and for a founder who’s looking to bet 10 years of their career on a make-or-break project, they can be daunting.

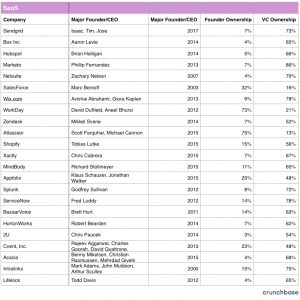

Crunchbase broke down the ownership structure of several companies at the time of their initial private offering, in an analysis that highlights the variability in outcomes for founders who raise external funds.

Out of a group of firms that went public, the median level of founder ownership was 15% and the mean was 21%. Sectors included social media, marketplaces, content distribution, gaming, payments, e-commerce, hardware, and SaaS (Software-as-a-Service).

As an example, take just one of the tables (below) as an example. Among the SaaS companies covered, Atlassian went public with founder ownership of 75% compared with 4% for Box Inc., 4% for Netsuite, and 3% for 2U. Not shown in the table below are some of the more successful celebrity founders had higher-than-average percentages. These included Amazon with 47% for the founding team, Overstock with 58% for the founders, 31% for Paige and Brin at Google, 24% for Hastings at Netflix, and Apple at 37% for Jobs and Co.

Balancing growth, cash flow, and risk should be the driving factors behind the specific fundraising path, but it shouldn’t come as a surprise that some of the most successful entrepreneurs of the last 25 years were able to do this parsimoniously – and it’s something all founders should seriously consider.

This is the second of a series of articles about startups and venture capital, where we’ll explain some of the concepts people might see discussed in the press. We’d love to hear your feedback.