Financial markets can be likened to the hot air that propels balloons. Markets get inflated by bullish commentary and the strong emotion of not wanting to be left behind by the “next big thing.” They deflate as a result of human emotions, not rational price setting structures.

The Financial Pipeline editors thought people would be interested in what a Markets COG (Certified Old Guy) had to say on the recent market volatility and asked me to write an article. They were taken a bit aback when I suggested they just rerun “A Hot Air Approach to the Markets” that I wrote for Finpipe in 1998, just before the Asian Contagion and Long Term Capital Management crises.

Being former newspaper journalists, the editors wanted something more up-to-date. I told them that the lesson of financial history is that market conniptions are just a part of the serial propensity of humans of doing the wrong thing at the wrong time. Humans have a basic urge to be part of things and not “lose out” when markets are hot and rising, but they flee in terror when prices fall.

We compromised by having me write an updated article with a long-term perspective on how the 2015 market turmoil tied into what has happened before.

When I wrote my original article in 1998, I had just started Canso Investment Counsel the year before. At that time, coming out of the real estate meltdown in the early 1990s, financial markets were on a tear, funded by then U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan’s serial rescues of anything that resembled a setback in financial asset prices. My experience in the markets had convinced me that most investors had no idea what they were doing and just followed the “investment fashion” of the day.

Credit spreads in early 1998 were at all-time expensive levels and financial market ebullience meant that the equity markets were on a tear. This astounded me, as people who had refused to accept any risk coming out of the early 1990s recession were now piling into very, very risky investments. “Wireless” company investments were in vogue and issuing junk bonds that paid no interest. I was telling anyone who bothered listening to sound advice that there was huge risk afoot and that the downside they were accepting was too high for the potential returns.

I then read a newspaper story on Richard Branson crashing a hot air balloon in Morocco. As a former RCAF air navigator, who did Search and Rescue, I was fascinated by the “uncontrollable” effect of the warming and cooling effect on his balloon’s envelope. When they lost control of the hot air that kept their balloon aloft, Branson and his partner either soared uncontrollably up or plunged dangerously in altitude over the Atlas Mountains in North Africa. They were very lucky to survive.

Branson and his crewmate must have been terrified because they were literally “along for the ride” in their out-of-control balloon. It struck me at the time that there was a great parallel to the then-soaring financial markets. Investors were pulled into the markets by the continuous bullish commentary and rising markets. They had to buy something –anything – and “get involved.” “A Hot Air Approach to the Markets” drew a very powerful image of soaring markets that, like Branson’s balloon, seemed unstoppable on the upside. But as I pointed out, the eventual plunge in markets would be equally terrifying on the downside.

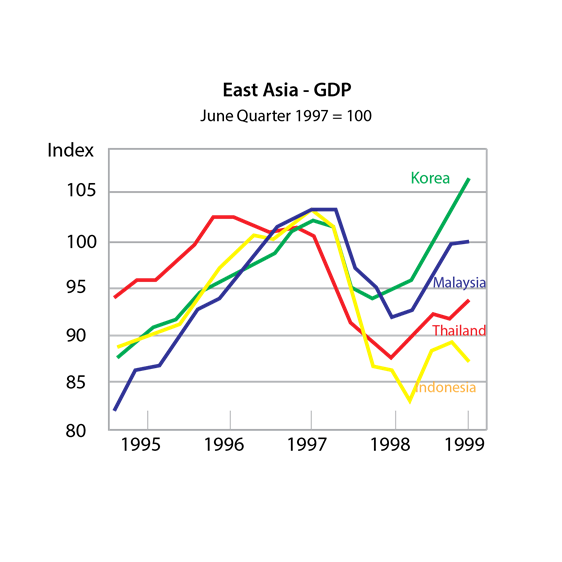

Despite the passage of 17 years, the markets of 1998 were eerily similar to those of 2015. The “Asian Tigers” were in vogue with immense money being directed into the emerging markets and commodities. Investors were drawn to risk like moths to flame and they couldn’t see any risk at all since the “obvious” upside was so huge. A bull market usually has a pretty simple but powerful sales pitch like, “The growth in China’s demand for commodities will be huge!” The “Asian Tigers” were the countries in Asia that had huge growth that everyone wanted to invest in. That is, until their growth stopped suddenly for apparently no reason with the “Asian Contagion” of 1998.

Nothing lasts forever, especially an investment mania. By the autumn of 1998, the emerging markets were melting down and the stock markets were plunging. The Nobel Laureates and finance professors who started the insanely levered Long Term Capital fund had just blown up. Of course, they were rescued in a deal brokered by the Greenspan Federal Reserve to avoid “financial contagion.”

So, what does this have to do with today? Well, let’s see, oil and other commodities melting down after a period of endlessly rising prices? Very smart people doing very stupid financial things? Emerging markets falling off a cliff with plunging currencies? Russia having an economic and currency meltdown? I could be describing the situation weighing on the markets in 2015. As the French say, “Plus ca change…”

The good news was that by 2000, markets were back to soaring up in value in the midst of the dot.com bubble. Of course they plummeted in 2000 but they were into a rising market by 2005 — which ended in the Credit Crunch of 2008. In 2009, people were so shell shocked that nobody could conceive of rising markets, which then proceeded to rise until they plummeted in 2011 during the Euro Debt Crisis.

Get the picture? Financial markets go up and down and reflect human emotions rather than the rational price setting structures of the efficient market theorists. I took modern finance as part of my MBA program in the mid 1980s, but soon saw it all repudiated in the actual financial markets.

The human instinct for “self preservation” is very powerful. It seemed to me that traders taking losses on their portfolios behaved very similarly to a defeated army fleeing in terror. Having graduated from Royal Military College, I had studied military psychology and understood that it took incredible discipline for an army not to flee a battle with casualties over 50 per cent. Watching traders flee from the market rout on Black Monday, October 19th 1987, made me believe that proper investment required discipline and an ability to invest when others were too afraid to.

It seemed that I was on to something as I watched portfolio managers and traders over the years. When I founded Canso, I structured our investment philosophy and portfolios to emphasize fundamental valuation and long-term thinking. The success of Canso is testament to the effectiveness of the investment doctrine that allows us to go against the prevailing investment fashions of the day.

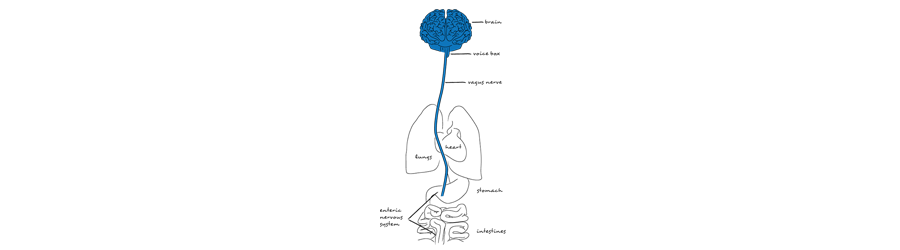

Academics are now starting to understand the human side of investment markets through the study of investor psychology and the development of the field of behavioural economics. This research shows that investors are not “rational,” as most theorists would have us believe. Some research, like the work described by Professor John Coates in the “Hour Between Dog and Wolf”, even now shows that humans are actually biologically hard-wired by hormones and chemicals to swing between being success drunk on testosterone in rising markets and catatonically depressed in falling markets.

So, what is an investor to do about turbulent markets? Actually, an investor should do absolutely nothing. A trader buys and sells things to make money. An investor invests in things that she or he should hold through thick and thin. If the underlying cash flows are sound, who cares what the price is doing in the short term.

In my experience, prices are set at the peak by the most naïve investor hoping to cash in after missing the boat on the way up. At the bottom, the most terrified seller who cannot countenance further losses sets the price.

A lot of the problem happens to be the media coverage, which is indeed “hot air.” The media wants to get attention, pure and simple. In ebullient markets, the talking heads chosen for interviews are those who are the most bullish, and those who spin tales of untold upside and riches. At the bottom, they are the doomsayers who predict the financial world will end.

In the middle of the Euro Debt Crisis of 2011, I made a breakfast presentation to a bunch of investment advisors. The first two speakers were economists who basically told the audience that things were really, really bad and could get much, much worse. Indeed, listening to them was a major depressive event. The audience, full of advisors whose clients were watching financial shows following the Slovenian Parliament’s potential veto of the rescue package, was morose if not catatonically despairing.

I got up and told the audience that I held a major position in European financials and that with the negative sentiment just expressed they had to be very, very cheap. Our position was reasoned and based on very substantial research. Things could go wrong, I explained, but we were well compensated for the risks we were taking. Guess who won the argument?

Our investment team is trained to go against the grain. Cheap investments are usually very unpopular and popular investments are very usually very expensive. What should you do to insulate yourself against the pro-cyclical nature of the financial media? Turn the channel from the constant financial media noise and don’t obsess about your portfolio statements. It is natural for people to seek control, but like Richard Branson and his balloon, market movements are uncontrollable.

Trying to time the markets is a fool’s errand. The trick is to find good investments and forget about the movement of the markets. All those people who sold out in 2009, vowing to never own another stock, missed most of the rally are probably now the ones chasing the markets now!