What’s the harm in urging the U.S. Federal Reserve to pursue expansionary monetary policy to achieve one’s Oval Office aspirations?

In short, mistimed interest rate cuts can fuel runaway inflation and throw economic decision-making into chaos.

The predictability of steady, modestly rising prices gives consumers and businesses the ability to plan for or finance, purchases, and to make investment decisions.

Inflation drives forward consumer purchases and puts off necessary capital investment.

I never promised you a rose garden

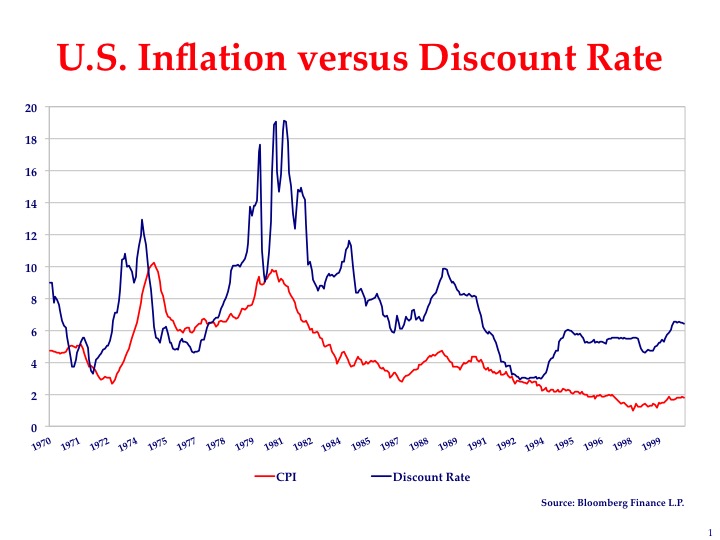

The chart below depicts U.S. inflation (red line) versus the Fed discount rate from 1970 to 2000.

In early 1972, then-U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Arthur Burns’ conciliatory easing contributed to U.S. GDP expansion of 9.4% annualized and helped former U.S. President Richard Nixon’s re-election effort.

Shortly thereafter, Nixon resigned and U.S. inflation rose dramatically. By 1974, U.S. GDP plunged into negative territory.

By February 1975, prices were increasing at a 10.2% annual pace and interest rates were substantially higher as well.

Not all the inflationary pressure can be attributed to Burns’ pressured rate cuts, but those cuts were certainly a significant factor in the economic upset of the ensuing decade.

By the time Burns’ tenure ended in early 1978, interest rates were on a rapidly escalating trajectory as the Fed sought to regain control of inflation and to achieve its mandate of stable prices.

Somebody needs to clean up this mess

Paul Volcker, Fed Chair from August 1979 to August 1987, raised rates on numerous occasions in his efforts to control inflation.

Those efforts took the discount rate to over 19% in March 1980.

In the second quarter of 1980, U.S. GDP contracted at an 8% annual rate. So important was the need to control inflation that Volcker and his Fed colleagues were willing to do whatever it took to rein in price pressures in the U.S. economy.