One of the more shocking revelations at the time of the 2008 financial crisis was how incredibly fragile the global banking system had become. Credit had become frozen amid fears about whether a bank that was a going concern Monday afternoon would be out of business the next morning.

Governments found they had to ride to the rescue of some of the biggest financial companies, including Royal Bank of Scotland, Wells Fargo and Bank of America. A notable exception was the big six Canadian banks. The government stood ready to provide support but none of the domestic banks needed the bail out.

“Fortunately, from a Canadian perspective, we had the strongest banking system in the world and we still continue to do so,” said Darren Hannah, vice-president of finance, risk and prudential policy at The Canadian Bankers Association.

“(The financial crisis of ’08) did expose that in other parts of the world in a number of banks there was weakness both from an investment banking and in some cases retail banking perspective. Basel III was the international regulatory community’s undertaking to try to address those weaknesses.”

Outside of Canada, taxpayers ended up footing bailout bills. But at the same time, regulators vowed that if ever a similar crisis recurred, the bank and its investors would feel a lot more of the pain.

And this is where the Basel III set of international banking regulations comes in. Developed by the Bank for International Settlements in the Swiss city that shares their name, the regulations spell out how banks must raise the amount of liquidity financial institutions have to keep on their banks. And just as important, they mandate a higher level of quality for that capital.

“It’s designed to improve banks’ quality of liquid assets available to them to deal with a financial downturn or a challenging financial market,” said Hannah.

“Part of that … is initiatives to ensure that in the event a bank finds itself in distress that the people who are taking the first loss on that are the investors and the institution itself.”

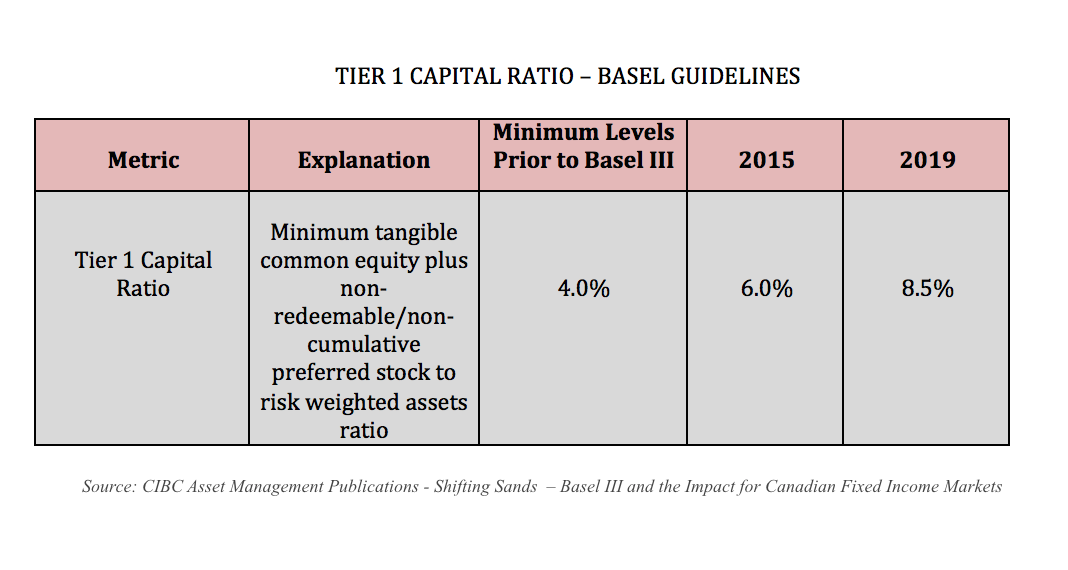

Banks have always had to keep a certain amount of assets available that can support the institution in the event of a crisis. Tier 1 requirements are the most well known and they contain cash reserves, common and preferred stock. Those requirements have been steadily rising.

There are further reserve Tiers. Tier 2 also measures a bank’s strength but the quality of capital in that tier isn’t as strong as the Tier 1 reserves. There has also been a Tier 3 but that is being phased out.

The minimum level for Tier 1 requirements prior to Basel III in 2010 – the Tier 1 Capital Ratio – was only four per cent. The level rose to six per cent in 2015 and to 8.5 per cent in 2019.

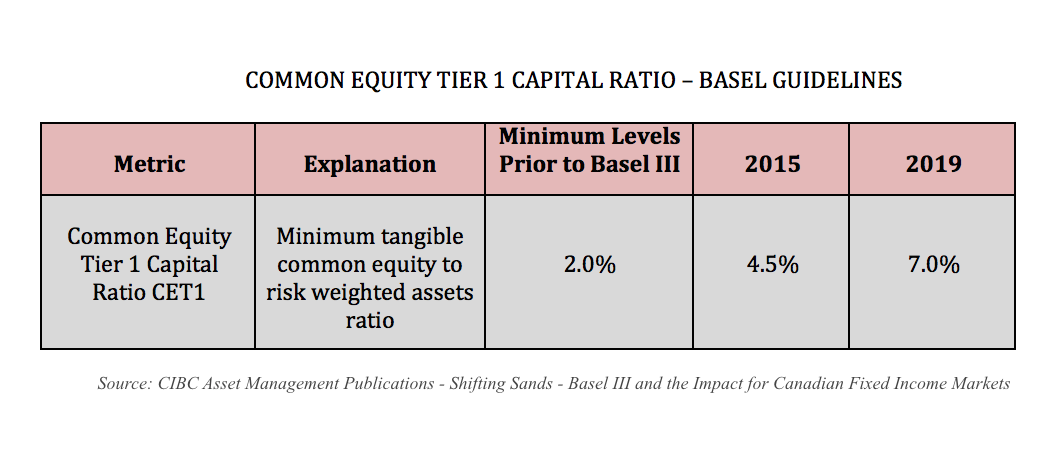

An important part of the Tier 1 requirements are what’s known as the “Core” or “Tangible Common Equity” component. This was as low as two per cent prior to Basel III but rose to 4.5 per cent in 2015 and seven per cent in 2019. Canadian banks face an eight per cent minimum as they have been designated Domestic Systemically Important Banks (D-SIBS).

At the same time, regulators deemed that the quality of assets in that Core would have to improve so that they could readily be converted to common shares.

The idea was that the Core should be comprised of a much greater amount of common equity and retained earnings.

For example, a bank’s own preferred shares could no longer be used in this core.

“For loss absorption, meaning that if the bank experiences a downturn, then that downturn can be passed along to the investor and (regulators) look for something that has no fixed charges, meaning the bank at its discretion can either maintain a payout to the investor or not,” added Hannah.

“That’s why they tend to like common shares more specifically on capital because it is the most loss absorbing, the most permanent and no fixed charge against it.”

Financial institutions in Canada and elsewhere have had to come up with a new family of securities to replace the ones that are no longer eligible as Tier 1 Capital. These fall into two categories – Non-Viability Contingent Capital (NVCC) and Convertible Contingent capital securities (CoCo’s).

These securities contain built-in triggers. In the case of NVCCs, they would convert to common equity when a bank reached a point of non-viability where the government would have to step up to run and bank and/or inject liquidity.

CoCo’s also convert to common equity (or are written down in value) but at an earlier point, when the bank is still operating as a going concern.

On top of the new Basel III guidelines, the Canadian government added another level of taxpayer protection from a crisis in the banking sector, known as bail-in provisions.

“What happens here is in the event that an institution reaches a certain point of non-viability or a trigger by the regulator (The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions, or OSFI) the long-term debt holders, meaning people who hold bank debt with a term in excess of 100 days, would be converted to common equity based on a predetermined formula,” explained Hannah.

One major effect of the introduction of a completely different capital structure for the banks has been a revision to the criteria of how ratings agencies rate the new NVCC and CoCo securities. And this has resulted in a series of downgrades by the major agencies of the Canadian banks.

But it’s important to note the downgrades have nothing to do with any deterioration of the credit quality of these institutions. Rather, they’re largely based on the conversion language of the new securities and concerns about how much aid governments would stump up in the event of a crisis, a quality known as government uplift.

However, these downgrades seem to have had a minimal impact on the Canadian TSX financial sector, which in mid-2016 was off less than five per cent from its 2014 level, before the collapse in oil prices started to impact the Canadian economy.

While there have been concerns about slower return-on-equity growth (reflecting a higher cost of capital), these seem to be balanced by the feeling that higher capital, liquidity and leverage standards enhance the already-strong Canadian banking system and reduce risks from a systemic or economic shock.