One of the many things that happened during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic was a search for context and perspective. Faced with a health crisis that forced the shutdown of the economy, people were left grasping for a comparison, or any perspective that would give them a sense of when this downturn would pass.

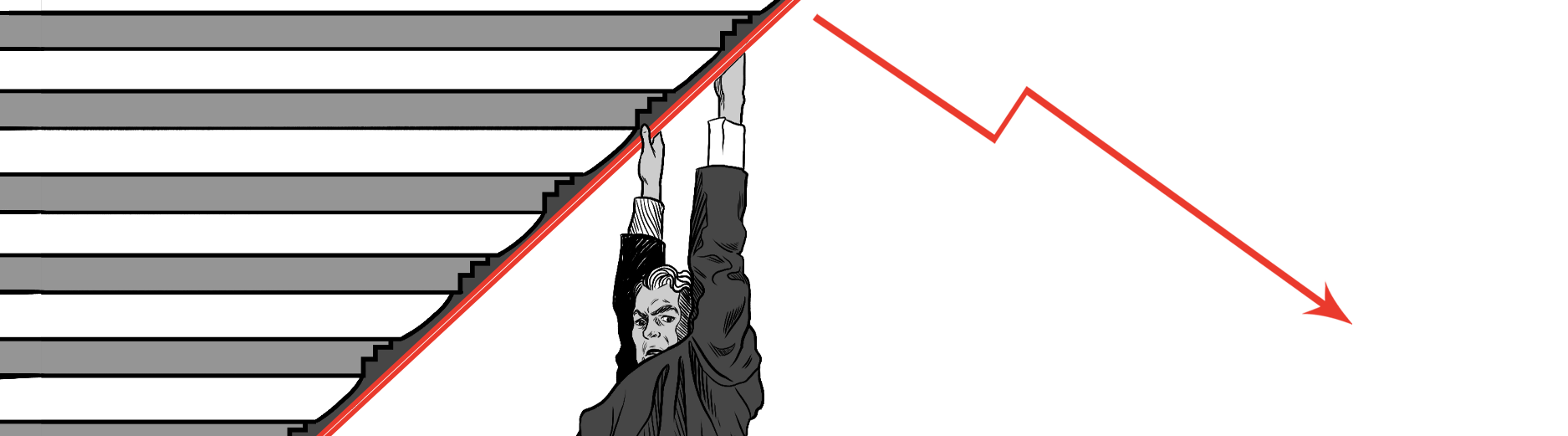

But as the days progressed it became increasingly obvious that there was no real comparison. As RBC put it in one of its economic notes, even before the first job numbers showed that in the first month of the pandemic one million people became unemployed, this was “a downturn like no other.”

And while that didn’t mean the crisis wouldn’t be resolved, it did make it more difficult to know when – and how – the economy would recover.

“This is the first recession that we’ve had that’s not been caused by the financial sector,” said Lindsay Tedds, an economics professor with the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy.

“We’re being asked how do we implement these public health measures, and that means essentially shutting down the economy. I, as an economist, have never been asked to shut down the economy. I’ve always been asked to do the opposite.”

While it may be tempting to point to the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918 when searching for similarities given that it was the last major global epidemic, that pandemic happened more than a century ago, and in very different conditions. It also wasn’t spread by the global nature of society but rather by soldiers returning home from the First World War.

“It happened at the end stages of a war, so it’s really hard to separate what the impacts of the flu were with the impacts of the war,” said Carolyn Whitzman, a visiting professor with the department of urban planning at the University of Ottawa.

“Economically, there was still a huge need for industrial production … and there was a labour shortage, so women got hired to fill the jobs that men couldn’t.”

The 2008 credit crunch also fails to stack up, because that crisis wasn’t driven by a health event that grounded economic activity but rather by overextended borrowers and problems in the financial system.

Similarly, the stock market crash that ushered in the Great Depression (perhaps the closest point of comparison in terms of the scale of job losses) isn’t a fair reflection, because it was the bursting of a financial bubble that precipitated that downturn.

“When we’re looking at the scale of both employment and economic contraction with this pandemic, when we compare it to Depression we’re using a scale we never even had to use (then),” Tedds said in an interview before March 2020 job numbers were announced.

“Quarterly GDP might be +10 to -10 per cent (but) we’re now looking at having to plug in perhaps maybe -50 per cent for contraction of GDP in a quarter. We’ve never had that on the scale before. We’ve never shed a million people from the labour force in a week before.”

What all these attempts at comparison point to, however, is that while we may not have seen a crisis quite like this one before, downturns themselves (and the stress and volatility they bring) aren’t uncommon – and they do pass.

“The pandemic part seems a bit unusual but the cyclic nature of global economies is really common (and) … there’s always some kind of precipitating circumstance,” said Whitzman.

“The question is how do you get out of it.”

In the 1930s for instance, public work projects provided employment. In 2008, U.S. banks received massive bailouts from the government to get back on track, which ushered in an era of quantitative easing that never really ended. In the early weeks of COVID-19, trillions of dollars were poured into the economy as banks and governments at all levels used every tool available in their monetary and fiscal policy arsenal to steer the financial system back on course and support people who’d lost their job as a result of the crisis.

While those measures seemed enough to temporarily calm markets and provide relief for people and families, at the time of writing, it was still too early to say what measures would help the economy bounce back in the long term – and what the full impact of pumping that level of liquidity into the financial ecosystem (at a time when central banks had been preparing to raise interest rates and roll back previous QE measures) would mean in the long run.

There were also questions about what the economy would look like once the recovery began. During COVID, areas such as groceries, basic services and pharmaceutical continued to grow, as people stocked up on food and other necessities, but sectors like hospitality, restaurants, trade and the arts suffered major losses. In an economy like Canada’s, which is predominantly service-based, those impacts cannot be underestimated.

“This economic recovery is going to look different because this contraction looks different,” said Tedds.

“How we go about slowly stimulating the economy, bringing everything online … I don’t think our usual bricks and mortar infrastructure policies are going to be what it is because the sectors that are being hit aren’t sectors that respond to bricks and mortar kind of projects.

We’re going to have to be open-minded and innovative and resourceful and hopefully (come up with solutions) working with data, provided that Stats Can can keep up with our data needs.”

And much like 2008 helped to highlight problems with the U.S. banking system, as experts look at ways to encourage a recovery, this crisis may also hold lessons around issues that should have been dealt with before the downturn.

“Crisis situations are often useful in highlighting big societal problems, and I think that’s been one of the aspects of the COVID coverage – the need for more investment on health care and also the need for more investment on housing,” said Whitzman.

“One of the things that’s coming out is that societies where governments know how to plan – including how to plan for disasters but knowing how to plan in general – have done fairly well.”

To Tedds, the immediate focus should be on making sure the right supports were in place to make sure people can afford to follow the public health guidance in order to avoid prolonging the circulation of the virus, which would prolong the economic problem.

“What all of this is doing is trying to keep people alive, and so it’s worth this economic pain,” she said.